Learning Content: Embracing the Chaos

Posted on Wednesday, June 16th, 2021 at 4:49 PM

Key Takeaways

- Forward-thinking L&D functions make the chaos of learning content work for their orgs. Being overwhelmed by the surging quantities, types, and sources of learning content is yesterday’s news—but still today’s problem. Learning leaders are embracing the chaos and moving from providing content to enabling it, with an eye toward making more content available to all employees.

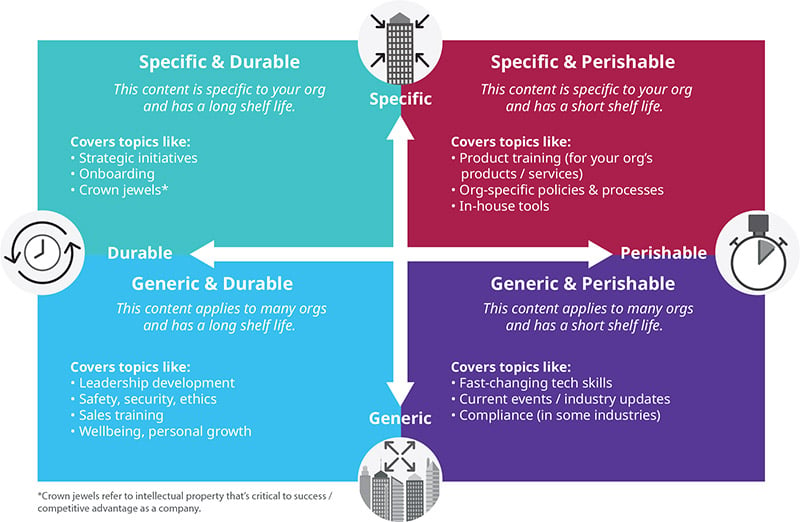

- Learning leaders should ask 2 questions about learning content: 1) Is it specific to the org? 2) How long is its shelf life (How durable is it)? Thinking in these 2 dimensions—specificity and durability—can help L&D functions clarify their learning content strategy and priorities.

- We developed a new model for learning content. From our conversations with forward-thinking learning leaders, we identified a model that breaks learning content into 4 categories (defined by the 2 dimensions of specificity and durability). This model can form the foundation of a learning content strategy that’s clear on priorities, roles & responsibilities, and areas of focus.

- There are distinct actions L&D functions can and should take to improve their learning content strategies—and those actions change based on the 4-category model of learning content introduced in this report. We provide some suggestions for immediate and longer-term actions to take, as well as examples of real orgs implementing these ideas, to help learning leaders organize the chaos and better manage learning content overall.

Why Talk About Learning Content Now?

We’ve been witnessing rapid growth in the amount of learning content available to employees. This growth started decades ago, but it’s recently turned from a trickle to a flood. There’s more learning content everywhere—inside and outside orgs; online and offline; on desktops and mobile devices; and in learning systems, shared folders, browsers, email, and chat platforms. Is it any wonder that employees are overwhelmed and exhausted by the sheer volume of all that’s available?1

Employees are overwhelmed and exhausted by the amount of learning content.

Employees feel like they’re drowning—and it’s L&D’s job to help them find and consume the content that builds skills and drives outcomes that matter to the business . To do this, L&D functions need well-crafted learning content strategies that support org learning and business strategies.

A learning content strategy should help L&D functions answer questions like:

- How will we decide what learning content to bring into the org?

- How will we identify—and help employees identify—learning content that’ll support our business and learning strategies?

- How and when will learning content be updated? By whom?

- How will we make the right learning content easily available to employees?

- What can we do immediately and in the longer term to improve employees’ ability to find and consume the learning content they need?

In this study—which included a lit review, roundtable, and interviews—we explored these questions. Through this research, we sought to identify the leading practices that orgs are using to help employees sift through the volume of learning content to find what’s right for them, when they need it.

L&D functions need well-crafted learning content strategies that support org learning and business strategies.

In the next section, we introduce the trends we uncovered as part of this study.

What’s Happening in Learning Content?

In the course of this research, we identified 4 trends in learning content that are helping shape the learning content strategies of forward-thinking orgs:

- More types and sources of learning content

- More enabling, less pushing of learning content by L&D functions

- More (and better) use of skills data to inform learning content priorities

- More access for all employees

In the following sections, we take a brief look at these 4 trends.

More types & sources of learning content

Not only is there more learning content in more places—but there are more types of content created by a wider variety of authors. Learning content used to be primarily created and controlled by L&D functions. Now, however, employees have access to:

- L&D function-created content

- Learning content created by subject-matter experts (SMEs)

- Company reports, policies, strategy docs, etc.

- Vendor-created learning content (custom or off the shelf)

- YouTube and other social media content

- Podcasts

- Conference notes, presentations, and videos

- Trade- or industry-specific content

- Learning content libraries (LinkedIn Learning, Udemy for Business, etc.)

- Subscriptions to learning content aggregators

- The entire internet

There’s not only more volume of content—there’s more types of content, in more places, created by a wider variety of authors.

And we know that’s not an exhaustive list.

The incredible volume, variety, and breadth of the learning content that’s available—over much of which L&D functions have limited control—complicate things for learning leaders and for employees.

Through our research, though, we found that learning leaders who’ve given this some thought don’t try to control the chaos. Instead, they embrace it—or, at least, they try to work with the reality that learning content is already complicated, and it’s only going to get bigger and more complex over time.

L&D functions can create systems, processes, and policies that help employees navigate the chaos of learning content.

Savvy learning leaders think about how to create systems, processes, and policies that help orgs and employees navigate through the chaos—rather than trying to tame the chaos itself (because that’s not gonna happen).

One learning leader noted:

“Learning functions need to recognize we never owned learning content in the first place, and we certainly don’t now. We need to embrace the chaos.”

Nick Halder, Senior Director of Talent, Snow Software

More enabling, less pushing by L&D functions

Given the increasing amount and variety of learning content out there, the move toward personalized development experiences, and the sheer variety of people in most orgs, it’s almost impossible for L&D functions to push the right content to the right people at the right time in the right format—all the time. There’s also a growing recognition that often the employee knows best—or at least has a good sense of—what they need to learn.

Learning leaders are thinking about how to enable employees to navigate to the right content themselves, rather than pushing content to employees.

Instead of trying to push learning content, L&D functions are thinking about how to enable employees to navigate to the right content themselves—by giving guidance and context about, for example, the org’s strategy and direction, skills that may be needed in the future, and how learning content is organized in the company. This guidance and context can create conditions that enable employees to find and consume learning content when and how they like, in ways that align with their needs and org goals.

More (& better) use of skills data to inform learning content priorities

Learning leaders we talked to noted that, in the past, L&D functions have sometimes pushed out learning content that wasn’t relevant or helpful to employees. These learning leaders see information about the skills employees and orgs need as a potential solution:

“Without insight into what skills are in demand and what skills people have, L&D tends to focus on the learning content we think people need. That’s rarely an effective approach.”

Participant, “New Trends in Learning Content & Content Management” Roundtable

Forward-thinking orgs are using information about the skills their workforce has and the skills it’ll need in the future to decide what learning content to prioritize. Learning leaders are making investments in learning content that can help close critical skills gaps.

Skills info can help orgs better understand what learning content to prioritize and invest in.

More access for all employees

In the last year or so, learning leaders have started taking a much closer look at how accessible learning content really is in their orgs: They’re recognizing the importance of making learning content more widely available to close skills gaps—and to help the business stay agile, responsive, and competitive.2

Three ways learning leaders can improve access include:

- Removing artificial barriers. Sometimes orgs give employees access to learning content on a “need-to-know” basis. But this logic creates unnecessary boundaries that could be removed unless they’re strategically justified—for example, intellectual property, safety / security, cost, or some other significant reason.

- Making learning content more discoverable. Sometimes great learning content is hidden in pockets or silos within the company. Orgs can find ways of making learning content easier to discover by implementing organization standards and really good search capabilities. They can also create a culture of discovery by removing unnecessary passwords and encouraging employees to poke around.

- Making learning content accessible on mobile. Learning content doesn’t just live on desktops anymore. Employees, particularly frontline workers, need access on their phones. This often means rethinking accessibility to LMSs or LXPs, as well as thinking mobile-first when creating new learning content.

Forward-thinking orgs are exploring ways to make learning content transparent, accessible, and appealing to all employees.

In brief

These 4 trends are currently shaping the learning content environment. In this research, we sought to understand how learning leaders are navigating these trends—and how these trends affect their goals, focus areas, challenges, and strategies for learning content.

We developed a learning content model that can help orgs think through their learning content strategies.

This inquiry resulted in a model that can help orgs think through their learning content strategies and make better decisions about where L&D functions should focus their time and resources. The next section introduces and explores this learning content model.

A Model for Thinking About Learning Content

We looked for similarities and differences between learning leaders’ approaches to learning content—and noticed that the learning leaders we spoke with take very different approaches to learning content based on 2 factors (or dimensions) of the learning content they’re working with:

- How unique the learning content is to their org (specificity). Are leaders dealing with learning content that applies specifically to their company or content that applies across orgs?

- The shelf life of the learning content (durability). Are leaders thinking mostly about learning content that needs to be updated rarely, or learning content that’s continually changing and regularly in jeopardy of being out of date? (Note: Long vs. short shelf life may differ from industry to industry and company to company. But, in general, we consider durable learning content to last 1 or more years without needing to be updated.)

If we plot learning content against these 2 dimensions (specificity and durability), then the content generally falls within 1 of the following 4 categories:

- Specific & Durable. Learning content that’s specific to 1 org and has a long shelf life

- Specific & Perishable. Learning content that’s specific to 1 org but changes often

- Generic & Perishable. Learning content that applies to many orgs and changes often

- Generic & Durable. Learning content that applies to many orgs and has a long shelf life

The learning content model, introduced in Figure 1, outlines these 4 categories and provides examples of some common topics that each category tends to cover.

Learning leaders might consider using this model to clarify the L&D function’s (and other stakeholders’) focus areas and roles regarding learning content. When we gave one learning leader—who happens to sit in a central L&D team within a federated system—a sneak peek at this model, he said:

“I like this model because it can help our L&D teams think about who owns what content. L&D sometimes tries to be all things to all people, but that’s not possible. In my company, we’re starting to be much more intentional about where each of our respective L&D teams are best-suited to play.”

John Z., Head of Digital Learning & Design, Global Medical Devices Company

Let’s look at each of these 4 categories in more detail. For each category, we discuss:

- The focus L&D functions should have for each learning content category

- Challenges specific to each learning content category

- How L&D functions can address those challenges in the immediate and longer terms

Specific & Durable

The Specific & Durable learning content category generally applies only to 1 org and has a relatively long shelf life. It tends to include:

The Specific & Durable learning content category generally applies only to 1 org and has a relatively long shelf life. It tends to include:

- Introductions to the org’s values, mission, philosophy, and how the org expects employees to act

- Info about strategic initiatives that define the org’s direction

- Onboarding training and materials

- “Crown jewels”—intellectual property that’s critical to success / competitive advantage as a company

The purpose of Specific & Durable learning content is often to shape organizational culture—helping employees understand “this is who we are” and “this is how we act.” Accordingly, the learning leaders we spoke with talked about Specific & Durable learning content most often in conjunction with organizational initiatives, such as organizational culture or change efforts; diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging (DEIB); and strategic pivots (e.g., adapting to industry upheaval).

Specific & Durable learning content often helps shape org culture—by helping employees understand “this is who we are” and “this is how we act.”

L&D’s focus should be: Drive organizational initiatives

Forward-thinking orgs conceptualize the L&D function’s role—and related goals—differently, depending on the category of learning content at hand: They have a different focus for each of the 4 categories of learning content. As the nature of the learning content and its associated challenges change, so does the way the org thinks about where L&D functions should spend the most effort.

L&D should think about how Specific & Durable learning content can help move the needle in areas that are priorities for the business.

For Specific & Durable learning content, L&D functions should focus on driving organizational initiatives. Specifically, they should think about how Specific & Durable learning content can help move the needle in areas that are priorities for the business.

As one learning leader said:

“What’s the strategic change that’s happening? Is your learning content relevant to get to those organizational outcomes?”

Participant, “New Trends in Learning Content & Content Management” Roundtable

Importantly, learning leaders aren’t thinking about how L&D functions can drive org initiatives alone—far from it. Almost every learning leader we spoke with about Specific & Durable learning content described how they’re reaching outside of the L&D function—to other parts of HR and to leaders of other functions—to stay in sync with org priorities and use learning content to support the cultural and strategic initiatives important to the business.

Biggest challenges we heard

Because Specific & Durable learning content often links directly to key business initiatives, L&D functions typically face challenges like:

- Staying aligned with business goals. How do we stay agile and aligned with business goals in an ever-flexible environment?

- Driving change. How do we use learning content to move the org toward its goals?

- Measuring impact. How do we know if the learning content is, in fact, driving the change, creating the culture, or moving the needle in ways that align with the org’s priorities?

Intentionally linking learning content to org priorities is a critical component in addressing these challenges, particularly around measuring impact.

Forward-thinking L&D functions measure success against metrics used by the entire org, not just the L&D function.

In our research on measuring learning impact, we found that average L&D functions tend to triage based on the squeakiest wheel or easiest fix. Conversely, more forward-thinking L&D functions develop strategies and relationships to continually align and adjust learning content to support org goals—and to measure success against metrics used by the entire org, not just the L&D function.3

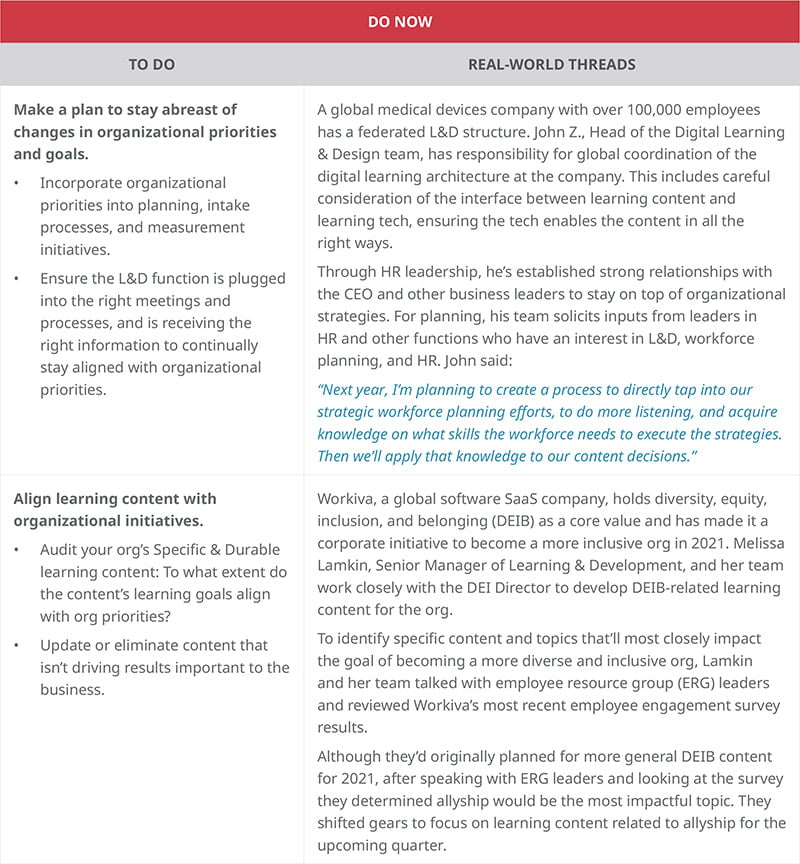

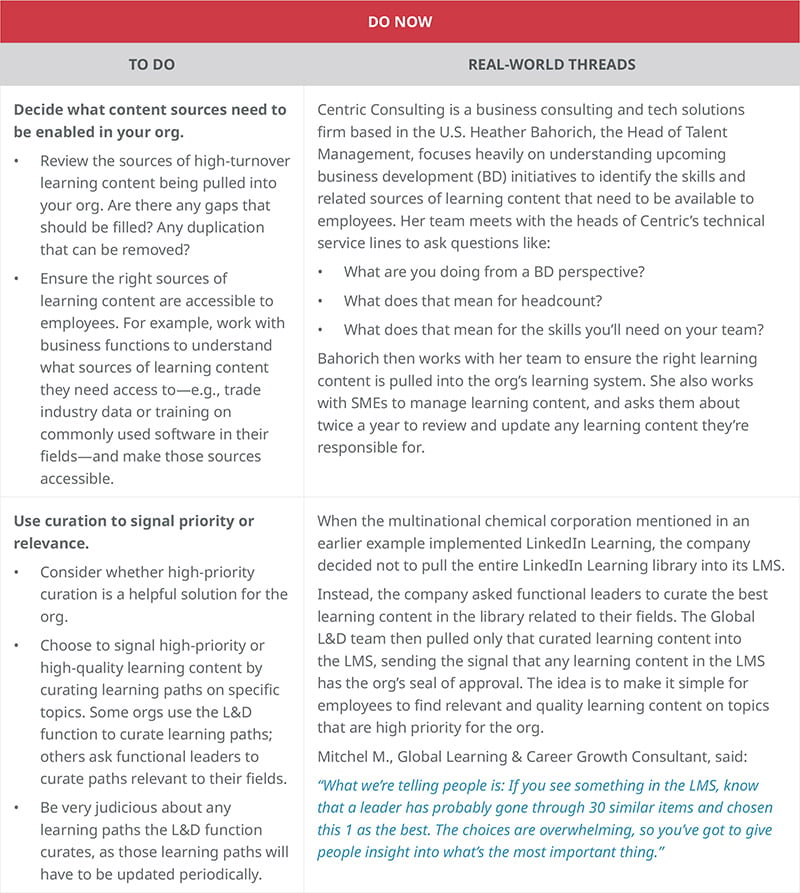

What L&D can do

In Figure 2, we include some ways L&D functions can start addressing these challenges. The ideas here (and in subsequent Figures 3-5) are divided into 2 sections:

- Do Now. Actions L&D functions can start on right away

- Work On. Actions requiring some time and coordination to implement

Each idea is paired with an example of how an org is implementing it.

Figure 2: Ways L&D Can Help Address Challenges—Specific & Durable Learning Content | Source: RedThread Research, 2021.

Specific & Perishable

Specific & Perishable learning content is unique to the org and changes / needs updating relatively often. Examples of this type of learning content include:

Specific & Perishable learning content is unique to the org and changes / needs updating relatively often. Examples of this type of learning content include:

- Customer training (e.g., on the org’s products)

- Org-specific policies and processes

- Instructions and updates on internally built software / tools

A defining characteristic of Specific & Perishable learning content: The sources of the learning content exist all over the org—in policy and process documents, product release notes, wikis, etc. This truth, combined with the fact that the content changes often, means it’s exceedingly difficult (if not impossible) for L&D functions to create and update all Specific & Perishable learning content needed by the org.

L&D’s focus should be: Enable content creation

In contrast to orgs in which the L&D function tries to control learning content, orgs that deputize all employees and focus on enabling the creation of learning content—no matter who does the creating—tend to have much more success ensuring that updated learning content is available when needed.

The L&D function’s focus for Specific & Perishable learning content should be to enable the creation and curation of learning content within the org—not to create or control that learning content.

The most forward-thinking learning leaders we encountered approach learning content almost as a free-market economy problem: In their minds, L&D functions should facilitate the supply and demand of learning content. Their job is to make those supply / demand exchanges as frictionless as possible, both for the consumers of the learning content as well as the suppliers, no matter where they sit in the org.

Biggest challenges we heard

Challenges with Specific & Perishable learning content tend to stem from the fact that it needs to be updated frequently and only internal people (for the most part) can do the updating. Challenges include:

- Learning content becomes stale and is hard to keep updated

- The best learning content exists in lots of different places in the org

- Quality and consistency of learning content can vary, since a lot of the learning content isn’t created by the L&D function

We talked with several learning leaders who said their L&D teams struggle either to keep tons of content updated themselves or to incentivize SMEs across the business to keep their learning content updated.

L&D functions should provide processes, templates, and guidance to enable anyone in the org to create or curate learning content with relative ease, consistency, and quality.

To address these challenges, the learning leaders we spoke with focus on putting in place processes, templates, and guidance that enable anyone in the org to create or curate learning content with relative ease, consistency, and quality.

For example, these forward-thinking learning leaders:

- Implement basic instructional design templates and norms across the org

- Put in place tech that offers standard templates, design principles, and formatting

- Track learning content usage and communicate regularly with learning content authors about updates

- Make themselves available as consultants—answering questions and providing advice on how to create effective learning content that meets the standards they’ve set

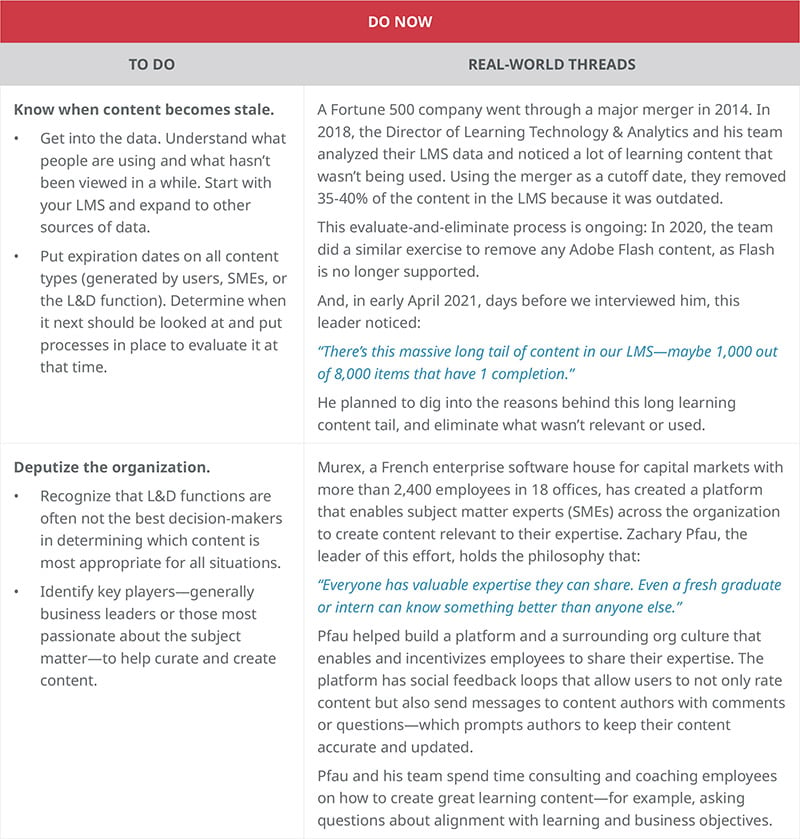

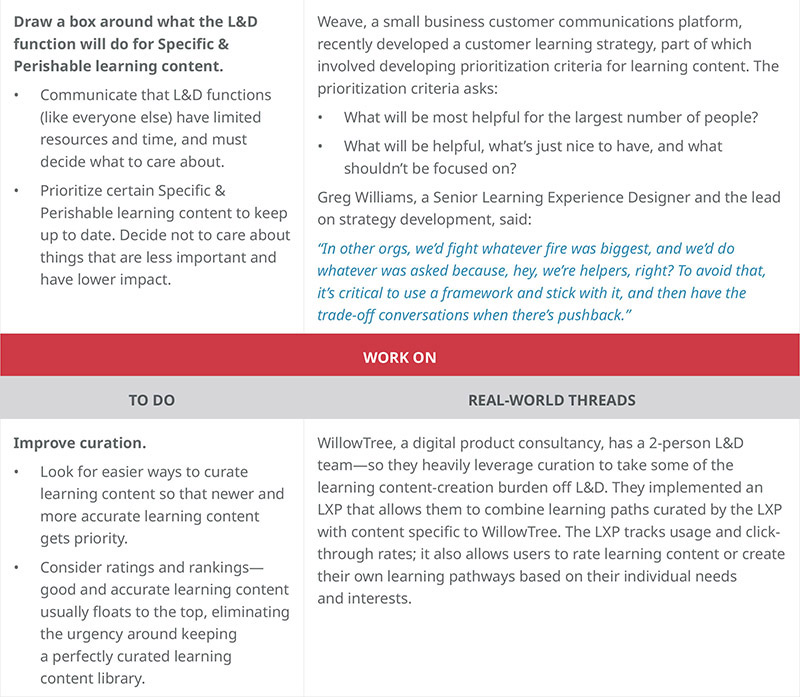

What L&D can do

In Figure 3, we include some ways L&D functions can start addressing these challenges. Each idea also outlines how an org is implementing that idea.

Figure 3: Ways L&D Can Help Address Challenges—Specific & Perishable Learning Content | Source: RedThread Research, 2021.4

Generic & Perishable

Generic & Perishable learning content can apply to many orgs but has a short shelf life. Examples of Generic & Perishable learning content include:

Generic & Perishable learning content can apply to many orgs but has a short shelf life. Examples of Generic & Perishable learning content include:

- Training / updates on fast-changing tech skills

- How-to tutorials on common processes (e.g., how to create a QR code, how to use a function in Excel)

- Info on current events and industry / market updates

Generic & Perishable learning content is defined by its sheer volume—and the fact that it’s everywhere.

The defining characteristic of this learning content category is sheer volume: There’s so much of it, everywhere! Much Generic & Perishable learning content is available for free online, although Google and YouTube are certainly not the only ways to find it. Other sources of Generic & Perishable learning content are, for example:

- Learning content libraries like PluralSight and LinkedIn Learning

- Professional or trade publications and websites

- Tech vendors offering learning content on how to use their software

Generic & Perishable learning content also changes frequently, meaning the great video someone found last year might be 3 releases out of date this year.

L&D’s focus should be: Help employees filter to the right learning content

The nature of Generic & Perishable learning content means L&D functions’ focus should be to help employees filter. It would be incredibly difficult to provide just the right info to each employee when they need it. Rather, learning leaders’ job is to create conditions that enable employees to cut through the noise and find what they need.

L&D functions should create conditions that enable employees to cut through the noise and volume of learning content to find what they need.

In most orgs, helping employees “filter” means using some kind of tech, most commonly an LXP. We’ve yet to see an org set up a completely manual process that enables filtering at the scale most orgs need: Most orgs leverage both tech and humans to get the job done. For example, teams may share the best or most helpful learning content with one another via Teams or Slack; they may set up queries in content aggregators like Feedly and other apps.

Biggest challenges we heard

We heard 2 main challenges related to Generic & Perishable learning content, both stemming from the volume and turnover common to this learning content category:

- There’s too much noise. For Generic & Perishable learning content, the “signal-to-noise” ratio is extremely low: There’s a lot of learning content in this category, but quality and relevance vary. Although it may be easy to find some learning content on a particular topic or question, it’s hard to know whether it’s the best learning content—or what the org would want an employee to rely on.

- Finding the latest and greatest. There’s regularly more and better learning content somewhere out there. Employees have a hard time finding the most updated, most relevant stuff.

Implementing effective search, curation, and recommendation engines can help give employees direction and a place to start.

Implementing effective search, curation, and recommendation engines can help address these challenges by giving employees direction and a place to start. We explore these ideas next.

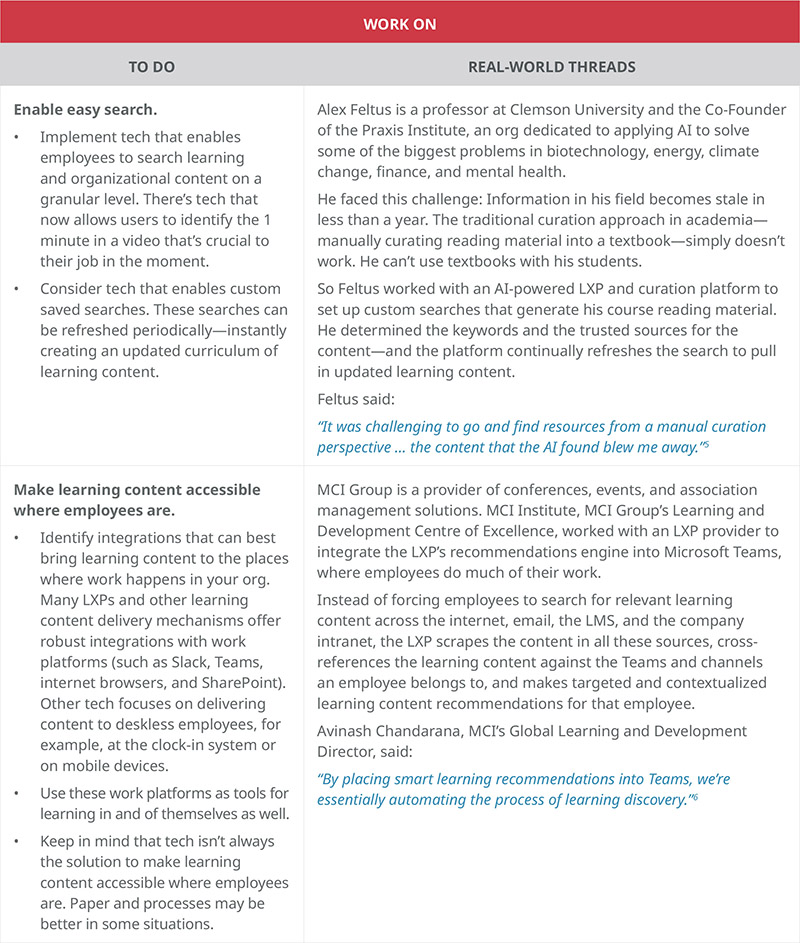

What L&D can do

In Figure 4, we include some ways L&D functions can start addressing these challenges. Each idea also outlines how an org is implementing that idea.

Figure 4: Ways L&D Can Help Address Challenges—Generic & Perishable Learning Content | Source: RedThread Research, 2021.5,6

Generic & Durable

Generic & Durable learning content changes relatively infrequently and applies to many orgs. It includes learning content such as:

Generic & Durable learning content changes relatively infrequently and applies to many orgs. It includes learning content such as:

- Education and refreshers on safety, security, and ethics

- Leadership development training and programs

- Industry-specific background / context (e.g., how the banking system works)

- Learning content to develop sales skills

- Support for employee wellbeing, mindfulness, and personal growth

Because Generic & Durable learning content can apply to many orgs and likely isn’t changing at a breakneck pace, quite a few learning content vendors play in this space. These vendors offer high-quality learning content on specialty topics that an in-house L&D team may not have the expertise or bandwidth to create.

Many Generic & Durable learning content vendors offer high-quality learning content on specialty topics that an in-house L&D team may not have the expertise or bandwidth to create.

L&D’s focus should be: Facilitate consistency & quality

L&D functions’ focus for Generic & Durable learning content should be facilitating consistency and quality—setting standards for what quality learning content looks like across the org. Because so many vendors offer different learning content at varying levels of quality, L&D functions can create value by helping the org define standards that outline, for example:

- The “go-to” vendors to work with on cross-functional topics like leadership, industry context, or wellbeing

- Criteria for selecting vendors not on the “go-to” list

- What high-quality learning content looks like and where it’s coming from

- Ways to measure / understand what learning content is working and what’s not

L&D functions should define standards that outline, for example, go-to vendors, vendor selection criteria, and what “high-quality” learning content looks like for the org.

With these standards (and / or others) in place, L&D functions can provide a consistent, org-wide point of view on cross-cutting topics, like “the way we lead,” “the way we think about safety,” and so on.

Biggest challenges we heard

Consistency and quality are the primary challenges for Generic & Durable learning content because much of the learning content can apply to many different functions (think leadership development or safety / security) and so many commercial sources of this category of learning content exist.

This breadth and variety give rise to potential differences—within the same org—in:

- The content that’s used for learning on a particular subject

- The quality or efficacy of that learning content

- How that learning content is delivered or supported

- Who gets access to the learning content

- The processes used to evaluate the learning content

As an example, we’ve seen orgs that use a dozen or more different leadership models because different functions / teams brought in different leadership vendors / consultants at different times.

Forward-thinking L&D functions consider how they can foster relationships—with vendors and other functions—to ensure consistency and quality of learning content across the org.

In the lit review we did as part of this research, we read several articles on creating consistent learning content. In an org, consistent course design and visual cues across as much learning content as possible can go a long way toward helping employees understand and navigate learning content easily. However, this kind of consistency is sometimes difficult to achieve with externally created content.

In addition to these instructional design elements, forward-thinking L&D functions are also considering how they can foster relationships—with vendors and with other functions—to bring people together across silos in order to ensure consistency and quality of learning content throughout the org. This sometimes means convening cross-functional groups to align on needs, pool resources, or negotiate org-level (rather than function- or team-level) contracts with vendors.

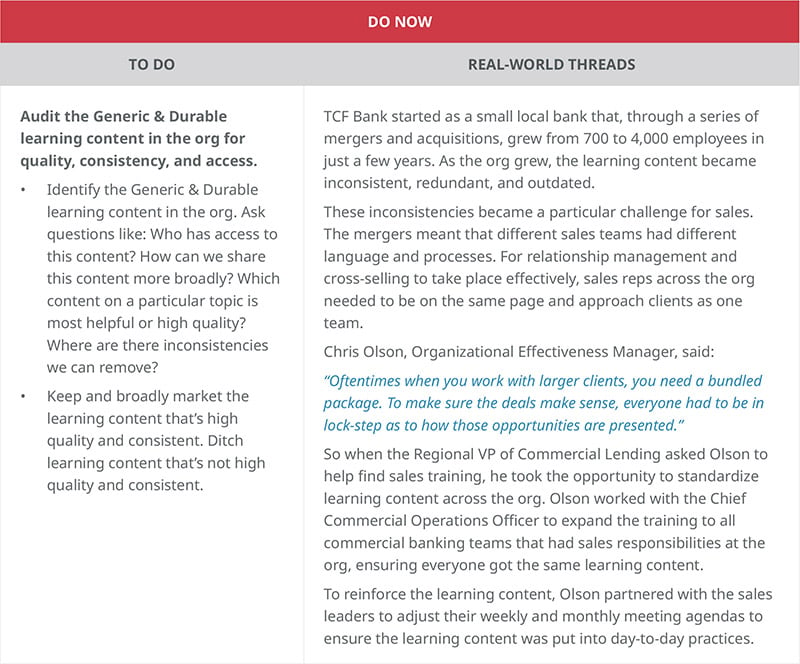

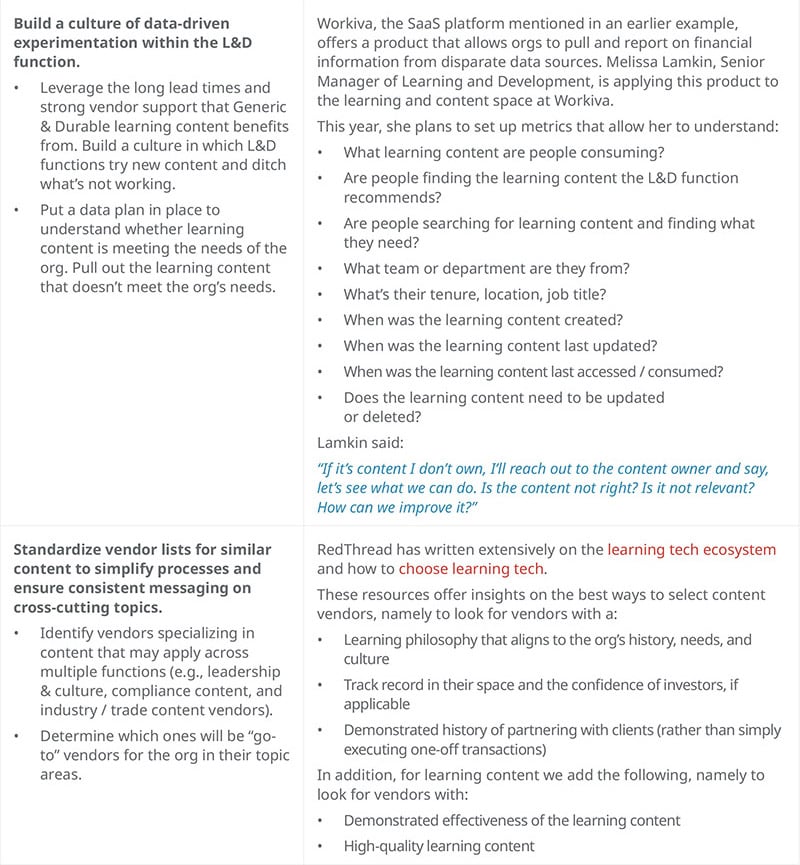

What L&D can do

In Figure 5, we include some ways L&D functions can start addressing these challenges. Each idea also outlines how an org is implementing that idea.

Figure 5: Ways L&D Can Help Address Challenges—Generic & Durable Learning Content | Source: RedThread Research, 2021.

Wrap-Up

We’ve given you a snapshot of recent trends in learning content, including how the explosion in volume and variety of learning content is affecting orgs and employees alike. We’ve also introduced a model for thinking about learning content in 4 categories, based on 2 key factors:

- The specificity of the learning content to the org

- The durability (or shelf life) of the learning content

Our biggest takeaway from this study is how the 4 different categories of learning content give rise to very different focuses for L&D functions—different conceptions of what L&D functions should do with regard to that learning content—and have very different associated challenges. (Unsurprisingly, there’s no one-size-fits-all learning content strategy.)

We are grateful to those learning leaders who shared their experiences and examples with us, and are excited to share so many concrete examples in this report.

As always, we welcome feedback and discussion! Please feel free to reach out to RedThread Research at [email protected] or www.redthreadresearch.com. We’d love to hear about your experiences.

Appendix 1: Research Methodology

We launched our study in Spring 2021. This report gathers and synthesizes findings from our research efforts, which include:

- A literature review of 51 articles from business, trade, and popular lit sources

- 1 roundtable with a total of 33 participants

- 15 in-depth interviews with learning leaders about their experiences and thoughts on learning content

For those looking for specific information that came out of those efforts, you’re in luck: We’ve a policy of sharing as much information as possible throughout the research process. Please see:

- Premise: “Content in the 2020s: Enabling Learning”

- Lit review: “Learning Content in the 2020s: What the Literature Says”

- Roundtable readout: “Trends in Learning Content & Content Management”

- Q&A call: "Learning Content"

Appendix 2: Contributors

Thank you so much to those of you who participated in our roundtable and interviews. We couldn’t have done this research without you! In addition to the leaders listed below, there are many others we can’t name publicly. We extend our gratitude nonetheless: You know who you are.

Angel Rodriguez

Ann Boldt

Brett Rose

Bria Dimke

Brian Richardson

Catherine Marchand

Chris Casement

Chris Olson

Clark Shah-Nelson

Eddie Garcia

Emily Crockett

Erik Soerhaug

Gordon O’Reilly

Greg Williams

Heather Bahorich

Ian Bolderstone

Jihyun Jeong

Jim Maddock

John Z.

Laurence D. Banner

Leah Holmgren

Marc Ramos

Martin Tanguay

Melissa Lamkin

Mitchel M.

Nick Halder

Nicole Leret

Robert Young

Sarah Foster

Shaun Rozyn

Stephanie Fritz

Stephen T.

Tania Tiippana

Tone Reierselmoen

Zachary Pfau

In addition, we thank Catherine Coughlin for editing the report, Jennifer Hines for graphics, Jenny Barandich for the layout, and Sana Lall-Trail for research and project management.

Learning Content: Embracing the Chaos

Posted on Tuesday, June 15th, 2021 at 10:29 AM

Key Takeaways

- Forward-thinking L&D functions make the chaos of learning content work for their orgs. Being overwhelmed by the surging quantities, types, and sources of learning content is yesterday’s news—but still today’s problem. Learning leaders are embracing the chaos and moving from providing content to enabling it, with an eye toward making more content available to all employees.

- Learning leaders should ask 2 questions about learning content: 1) Is it specific to the org? 2) How long is its shelf life (How durable is it)? Thinking in these 2 dimensions—specificity and durability—can help L&D functions clarify their learning content strategy and priorities.

- We developed a new model for learning content. From our conversations with forward-thinking learning leaders, we identified a model that breaks learning content into 4 categories (defined by the 2 dimensions of specificity and durability). This model can form the foundation of a learning content strategy that’s clear on priorities, roles & responsibilities, and areas of focus.

- There are distinct actions L&D functions can and should take to improve their learning content strategies—and those actions change based on the 4-category model of learning content introduced in this report. We provide some suggestions for immediate and longer-term actions to take, as well as examples of real orgs implementing these ideas, to help learning leaders organize the chaos and better manage learning content overall.

Why Talk About Learning Content Now?

We’ve been witnessing rapid growth in the amount of learning content available to employees. This growth started decades ago, but it’s recently turned from a trickle to a flood. There’s more learning content everywhere—inside and outside orgs; online and offline; on desktops and mobile devices; and in learning systems, shared folders, browsers, email, and chat platforms. Is it any wonder that employees are overwhelmed and exhausted by the sheer volume of all that’s available?1

Employees are overwhelmed and exhausted by the amount of learning content.

Employees feel like they’re drowning—and it’s L&D’s job to help them find and consume the content that builds skills and drives outcomes that matter to the business. To do this, L&D functions need well-crafted learning content strategies that support org learning and business strategies.

A learning content strategy should help L&D functions answer questions like:

- How will we decide what learning content to bring into the org?

- How will we identify—and help employees identify—learning content that’ll support our business and learning strategies?

- How and when will learning content be updated? By whom?

- How will we make the right learning content easily available to employees?

- What can we do immediately and in the longer term to improve employees’ ability to find and consume the learning content they need?

In this study—which included a lit review, roundtable, and interviews—we explored these questions. Through this research, we sought to identify the leading practices that orgs are using to help employees sift through the volume of learning content to find what’s right for them, when they need it.

L&D functions need well-crafted learning content strategies that support org learning and business strategies.

In the next section, we introduce the trends we uncovered as part of this study.

What’s Happening in Learning Content?

In the course of this research, we identified 4 trends in learning content that are helping shape the learning content strategies of forward-thinking orgs:

- More types and sources of learning content

- More enabling, less pushing of learning content by L&D functions

- More (and better) use of skills data to inform learning content priorities

- More access for all employees

In the following sections, we take a brief look at these 4 trends.

More types & sources of learning content

Not only is there more learning content in more places—but there are more types of content created by a wider variety of authors. Learning content used to be primarily created and controlled by L&D functions. Now, however, employees have access to:

- L&D function-created content

- Learning content created by subject-matter experts (SMEs)

- Company reports, policies, strategy docs, etc.

- Vendor-created learning content (custom or off the shelf)

- YouTube and other social media content

- Podcasts

- Conference notes, presentations, and videos

- Trade- or industry-specific content

- Learning content libraries (LinkedIn Learning, Udemy for Business, etc.)

- Subscriptions to learning content aggregators

- The entire internet

There’s not only more volume of content—there’s more types of content, in more places, created by a wider variety of authors.

And we know that’s not an exhaustive list.

The incredible volume, variety, and breadth of the learning content that’s available—over much of which L&D functions have limited control—complicate things for learning leaders and for employees.

Through our research, though, we found that learning leaders who’ve given this some thought don’t try to control the chaos. Instead, they embrace it—or, at least, they try to work with the reality that learning content is already complicated, and it’s only going to get bigger and more complex over time.

L&D functions can create systems, processes, and policies that help employees navigate the chaos of learning content.

Savvy learning leaders think about how to create systems, processes, and policies that help orgs and employees navigate through the chaos—rather than trying to tame the chaos itself (because that’s not gonna happen).

One learning leader noted:

“Learning functions need to recognize we never owned learning content in the first place, and we certainly don’t now. We need to embrace the chaos.”

Nick Halder, Senior Director of Talent, Snow Software

More enabling, less pushing by L&D functions

Given the increasing amount and variety of learning content out there, the move toward personalized development experiences, and the sheer variety of people in most orgs, it’s almost impossible for L&D functions to push the right content to the right people at the right time in the right format—all the time. There’s also a growing recognition that often the employee knows best—or at least has a good sense of—what they need to learn.

Learning leaders are thinking about how to enable employees to navigate to the right content themselves, rather than pushing content to employees.

Instead of trying to push learning content, L&D functions are thinking about how to enable employees to navigate to the right content themselves—by giving guidance and context about, for example, the org’s strategy and direction, skills that may be needed in the future, and how learning content is organized in the company. This guidance and context can create conditions that enable employees to find and consume learning content when and how they like, in ways that align with their needs and org goals.

More (& better) use of skills data to inform learning content priorities

Learning leaders we talked to noted that, in the past, L&D functions have sometimes pushed out learning content that wasn’t relevant or helpful to employees. These learning leaders see information about the skills employees and orgs need as a potential solution:

“Without insight into what skills are in demand and what skills people have, L&D tends to focus on the learning content we think people need. That’s rarely an effective approach.”

Participant, “New Trends in Learning Content & Content Management” Roundtable

Forward-thinking orgs are using information about the skills their workforce has and the skills it’ll need in the future to decide what learning content to prioritize. Learning leaders are making investments in learning content that can help close critical skills gaps.

Skills info can help orgs better understand what learning content to prioritize and invest in.

More access for all employees

In the last year or so, learning leaders have started taking a much closer look at how accessible learning content really is in their orgs: They’re recognizing the importance of making learning content more widely available to close skills gaps—and to help the business stay agile, responsive, and competitive.2

Three ways learning leaders can improve access include:

- Removing artificial barriers. Sometimes orgs give employees access to learning content on a “need-to-know” basis. But this logic creates unnecessary boundaries that could be removed unless they’re strategically justified—for example, intellectual property, safety / security, cost, or some other significant reason.

- Making learning content more discoverable. Sometimes great learning content is hidden in pockets or silos within the company. Orgs can find ways of making learning content easier to discover by implementing organization standards and really good search capabilities. They can also create a culture of discovery by removing unnecessary passwords and encouraging employees to poke around.

- Making learning content accessible on mobile. Learning content doesn’t just live on desktops anymore. Employees, particularly frontline workers, need access on their phones. This often means rethinking accessibility to LMSs or LXPs, as well as thinking mobile-first when creating new learning content.

Forward-thinking orgs are exploring ways to make learning content transparent, accessible, and appealing to all employees.

In brief

These 4 trends are currently shaping the learning content environment. In this research, we sought to understand how learning leaders are navigating these trends—and how these trends affect their goals, focus areas, challenges, and strategies for learning content.

We developed a learning content model that can help orgs think through their learning content strategies.

This inquiry resulted in a model that can help orgs think through their learning content strategies and make better decisions about where L&D functions should focus their time and resources. The next section introduces and explores this learning content model.

A Model for Thinking About Learning Content

We looked for similarities and differences between learning leaders’ approaches to learning content—and noticed that the learning leaders we spoke with take very different approaches to learning content based on 2 factors (or dimensions) of the learning content they’re working with:

- How unique the learning content is to their org (specificity). Are leaders dealing with learning content that applies specifically to their company or content that applies across orgs?

- The shelf life of the learning content (durability). Are leaders thinking mostly about learning content that needs to be updated rarely, or learning content that’s continually changing and regularly in jeopardy of being out of date? (Note: Long vs. short shelf life may differ from industry to industry and company to company. But, in general, we consider durable learning content to last 1 or more years without needing to be updated.)

If we plot learning content against these 2 dimensions (specificity and durability), then the content generally falls within 1 of the following 4 categories:

- Specific & Durable. Learning content that’s specific to 1 org and has a long shelf life

- Specific & Perishable. Learning content that’s specific to 1 org but changes often

- Generic & Perishable. Learning content that applies to many orgs and changes often

- Generic & Durable. Learning content that applies to many orgs and has a long shelf life

The learning content model, introduced in Figure 1, outlines these 4 categories and provides examples of some common topics that each category tends to cover.

Learning leaders might consider using this model to clarify the L&D function’s (and other stakeholders’) focus areas and roles regarding learning content. When we gave one learning leader—who happens to sit in a central L&D team within a federated system—a sneak peek at this model, he said:

“I like this model because it can help our L&D teams think about who owns what content. L&D sometimes tries to be all things to all people, but that’s not possible. In my company, we’re starting to be much more intentional about where each of our respective L&D teams are best-suited to play.”

John Z., Head of Digital Learning & Design, Global Medical Devices Company

Let’s look at each of these 4 categories in more detail. For each category, we discuss:

- The focus L&D functions should have for each learning content category

- Challenges specific to each learning content category

- How L&D functions can address those challenges in the immediate and longer terms

Specific & Durable

The Specific & Durable learning content category generally applies only to 1 org and has a relatively long shelf life. It tends to include:

The Specific & Durable learning content category generally applies only to 1 org and has a relatively long shelf life. It tends to include:

- Introductions to the org’s values, mission, philosophy, and how the org expects employees to act

- Info about strategic initiatives that define the org’s direction

- Onboarding training and materials

- “Crown jewels”—intellectual property that’s critical to success / competitive advantage as a company

The purpose of Specific & Durable learning content is often to shape organizational culture—helping employees understand “this is who we are” and “this is how we act.” Accordingly, the learning leaders we spoke with talked about Specific & Durable learning content most often in conjunction with organizational initiatives, such as organizational culture or change efforts; diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging (DEIB); and strategic pivots (e.g., adapting to industry upheaval).

Specific & Durable learning content often helps shape org culture—by helping employees understand “this is who we are” and “this is how we act.”

L&D’s focus should be: Drive organizational initiatives

Forward-thinking orgs conceptualize the L&D function’s role—and related goals—differently, depending on the category of learning content at hand: They have a different focus for each of the 4 categories of learning content. As the nature of the learning content and its associated challenges change, so does the way the org thinks about where L&D functions should spend the most effort.

L&D should think about how Specific & Durable learning content can help move the needle in areas that are priorities for the business.

For Specific & Durable learning content, L&D functions should focus on driving organizational initiatives. Specifically, they should think about how Specific & Durable learning content can help move the needle in areas that are priorities for the business.

As one learning leader said:

“What’s the strategic change that’s happening? Is your learning content relevant to get to those organizational outcomes?”

Participant, “New Trends in Learning Content & Content Management” Roundtable

Importantly, learning leaders aren’t thinking about how L&D functions can drive org initiatives alone—far from it. Almost every learning leader we spoke with about Specific & Durable learning content described how they’re reaching outside of the L&D function—to other parts of HR and to leaders of other functions—to stay in sync with org priorities and use learning content to support the cultural and strategic initiatives important to the business.

Biggest challenges we heard

Because Specific & Durable learning content often links directly to key business initiatives, L&D functions typically face challenges like:

- Staying aligned with business goals. How do we stay agile and aligned with business goals in an ever-flexible environment?

- Driving change. How do we use learning content to move the org toward its goals?

- Measuring impact. How do we know if the learning content is, in fact, driving the change, creating the culture, or moving the needle in ways that align with the org’s priorities?

Intentionally linking learning content to org priorities is a critical component in addressing these challenges, particularly around measuring impact.

Forward-thinking L&D functions measure success against metrics used by the entire org, not just the L&D function.

In our research on measuring learning impact, we found that average L&D functions tend to triage based on the squeakiest wheel or easiest fix. Conversely, more forward-thinking L&D functions develop strategies and relationships to continually align and adjust learning content to support org goals—and to measure success against metrics used by the entire org, not just the L&D function.3

What L&D can do

In Figure 2, we include some ways L&D functions can start addressing these challenges. The ideas here (and in subsequent Figures 3-5) are divided into 2 sections:

- Do Now. Actions L&D functions can start on right away

- Work On. Actions requiring some time and coordination to implement

Each idea is paired with an example of how an org is implementing it.

Figure 2: Ways L&D Can Help Address Challenges—Specific & Durable Learning Content | Source: RedThread Research, 2021.

Specific & Perishable

Specific & Perishable learning content is unique to the org and changes / needs updating relatively often. Examples of this type of learning content include:

Specific & Perishable learning content is unique to the org and changes / needs updating relatively often. Examples of this type of learning content include:

- Customer training (e.g., on the org’s products)

- Org-specific policies and processes

- Instructions and updates on internally built software / tools

A defining characteristic of Specific & Perishable learning content: The sources of the learning content exist all over the org—in policy and process documents, product release notes, wikis, etc. This truth, combined with the fact that the content changes often, means it’s exceedingly difficult (if not impossible) for L&D functions to create and update all Specific & Perishable learning content needed by the org.

L&D’s focus should be: Enable content creation

In contrast to orgs in which the L&D function tries to control learning content, orgs that deputize all employees and focus on enabling the creation of learning content—no matter who does the creating—tend to have much more success ensuring that updated learning content is available when needed.

The L&D function’s focus for Specific & Perishable learning content should be to enable the creation and curation of learning content within the org—not to create or control that learning content.

The most forward-thinking learning leaders we encountered approach learning content almost as a free-market economy problem: In their minds, L&D functions should facilitate the supply and demand of learning content. Their job is to make those supply / demand exchanges as frictionless as possible, both for the consumers of the learning content as well as the suppliers, no matter where they sit in the org.

Biggest challenges we heard

Challenges with Specific & Perishable learning content tend to stem from the fact that it needs to be updated frequently and only internal people (for the most part) can do the updating. Challenges include:

- Learning content becomes stale and is hard to keep updated

- The best learning content exists in lots of different places in the org

- Quality and consistency of learning content can vary, since a lot of the learning content isn’t created by the L&D function

We talked with several learning leaders who said their L&D teams struggle either to keep tons of content updated themselves or to incentivize SMEs across the business to keep their learning content updated.

L&D functions should provide processes, templates, and guidance to enable anyone in the org to create or curate learning content with relative ease, consistency, and quality.

To address these challenges, the learning leaders we spoke with focus on putting in place processes, templates, and guidance that enable anyone in the org to create or curate learning content with relative ease, consistency, and quality.

For example, these forward-thinking learning leaders:

- Implement basic instructional design templates and norms across the org

- Put in place tech that offers standard templates, design principles, and formatting

- Track learning content usage and communicate regularly with learning content authors about updates

- Make themselves available as consultants—answering questions and providing advice on how to create effective learning content that meets the standards they’ve set

What L&D can do

In Figure 3, we include some ways L&D functions can start addressing these challenges. Each idea also outlines how an org is implementing that idea.

Figure 3: Ways L&D Can Help Address Challenges—Specific & Perishable Learning Content | Source: RedThread Research, 2021.4

Generic & Perishable

Generic & Perishable learning content can apply to many orgs but has a short shelf life. Examples of Generic & Perishable learning content include:

Generic & Perishable learning content can apply to many orgs but has a short shelf life. Examples of Generic & Perishable learning content include:

- Training / updates on fast-changing tech skills

- How-to tutorials on common processes (e.g., how to create a QR code, how to use a function in Excel)

- Info on current events and industry / market updates

Generic & Perishable learning content is defined by its sheer volume—and the fact that it’s everywhere.

The defining characteristic of this learning content category is sheer volume: There’s so much of it, everywhere! Much Generic & Perishable learning content is available for free online, although Google and YouTube are certainly not the only ways to find it. Other sources of Generic & Perishable learning content are, for example:

- Learning content libraries like PluralSight and LinkedIn Learning

- Professional or trade publications and websites

- Tech vendors offering learning content on how to use their software

Generic & Perishable learning content also changes frequently, meaning the great video someone found last year might be 3 releases out of date this year.

L&D’s focus should be: Help employees filter to the right learning content

The nature of Generic & Perishable learning content means L&D functions’ focus should be to help employees filter. It would be incredibly difficult to provide just the right info to each employee when they need it. Rather, learning leaders’ job is to create conditions that enable employees to cut through the noise and find what they need.

L&D functions should create conditions that enable employees to cut through the noise and volume of learning content to find what they need.

In most orgs, helping employees “filter” means using some kind of tech, most commonly an LXP. We’ve yet to see an org set up a completely manual process that enables filtering at the scale most orgs need: Most orgs leverage both tech and humans to get the job done. For example, teams may share the best or most helpful learning content with one another via Teams or Slack; they may set up queries in content aggregators like Feedly and other apps.

Biggest challenges we heard

We heard 2 main challenges related to Generic & Perishable learning content, both stemming from the volume and turnover common to this learning content category:

- There’s too much noise. For Generic & Perishable learning content, the “signal-to-noise” ratio is extremely low: There’s a lot of learning content in this category, but quality and relevance vary. Although it may be easy to find some learning content on a particular topic or question, it’s hard to know whether it’s the best learning content—or what the org would want an employee to rely on.

- Finding the latest and greatest. There’s regularly more and better learning content somewhere out there. Employees have a hard time finding the most updated, most relevant stuff.

Implementing effective search, curation, and recommendation engines can help give employees direction and a place to start.

Implementing effective search, curation, and recommendation engines can help address these challenges by giving employees direction and a place to start. We explore these ideas next.

What L&D can do

In Figure 4, we include some ways L&D functions can start addressing these challenges. Each idea also outlines how an org is implementing that idea.

Figure 4: Ways L&D Can Help Address Challenges—Generic & Perishable Learning Content | Source: RedThread Research, 2021.5,6

Generic & Durable

Generic & Durable learning content changes relatively infrequently and applies to many orgs. It includes learning content such as:

Generic & Durable learning content changes relatively infrequently and applies to many orgs. It includes learning content such as:

- Education and refreshers on safety, security, and ethics

- Leadership development training and programs

- Industry-specific background / context (e.g., how the banking system works)

- Learning content to develop sales skills

- Support for employee wellbeing, mindfulness, and personal growth

Because Generic & Durable learning content can apply to many orgs and likely isn’t changing at a breakneck pace, quite a few learning content vendors play in this space. These vendors offer high-quality learning content on specialty topics that an in-house L&D team may not have the expertise or bandwidth to create.

Many Generic & Durable learning content vendors offer high-quality learning content on specialty topics that an in-house L&D team may not have the expertise or bandwidth to create.

L&D’s focus should be: Facilitate consistency & quality

L&D functions’ focus for Generic & Durable learning content should be facilitating consistency and quality—setting standards for what quality learning content looks like across the org. Because so many vendors offer different learning content at varying levels of quality, L&D functions can create value by helping the org define standards that outline, for example:

- The “go-to” vendors to work with on cross-functional topics like leadership, industry context, or wellbeing

- Criteria for selecting vendors not on the “go-to” list

- What high-quality learning content looks like and where it’s coming from

- Ways to measure / understand what learning content is working and what’s not

L&D functions should define standards that outline, for example, go-to vendors, vendor selection criteria, and what “high-quality” learning content looks like for the org.

With these standards (and / or others) in place, L&D functions can provide a consistent, org-wide point of view on cross-cutting topics, like “the way we lead,” “the way we think about safety,” and so on.

Biggest challenges we heard

Consistency and quality are the primary challenges for Generic & Durable learning content because much of the learning content can apply to many different functions (think leadership development or safety / security) and so many commercial sources of this category of learning content exist.

This breadth and variety give rise to potential differences—within the same org—in:

- The content that’s used for learning on a particular subject

- The quality or efficacy of that learning content

- How that learning content is delivered or supported

- Who gets access to the learning content

- The processes used to evaluate the learning content

As an example, we’ve seen orgs that use a dozen or more different leadership models because different functions / teams brought in different leadership vendors / consultants at different times.

Forward-thinking L&D functions consider how they can foster relationships—with vendors and other functions—to ensure consistency and quality of learning content across the org.

In the lit review we did as part of this research, we read several articles on creating consistent learning content. In an org, consistent course design and visual cues across as much learning content as possible can go a long way toward helping employees understand and navigate learning content easily. However, this kind of consistency is sometimes difficult to achieve with externally created content.

In addition to these instructional design elements, forward-thinking L&D functions are also considering how they can foster relationships—with vendors and with other functions—to bring people together across silos in order to ensure consistency and quality of learning content throughout the org. This sometimes means convening cross-functional groups to align on needs, pool resources, or negotiate org-level (rather than function- or team-level) contracts with vendors.

What L&D can do

In Figure 5, we include some ways L&D functions can start addressing these challenges. Each idea also outlines how an org is implementing that idea.

Figure 5: Ways L&D Can Help Address Challenges—Generic & Durable Learning Content | Source: RedThread Research, 2021.

Wrap-Up

We’ve given you a snapshot of recent trends in learning content, including how the explosion in volume and variety of learning content is affecting orgs and employees alike. We’ve also introduced a model for thinking about learning content in 4 categories, based on 2 key factors:

- The specificity of the learning content to the org

- The durability (or shelf life) of the learning content

Our biggest takeaway from this study is how the 4 different categories of learning content give rise to very different focuses for L&D functions—different conceptions of what L&D functions should do with regard to that learning content—and have very different associated challenges. (Unsurprisingly, there’s no one-size-fits-all learning content strategy.)

We are grateful to those learning leaders who shared their experiences and examples with us, and are excited to share so many concrete examples in this report.

As always, we welcome feedback and discussion! Please feel free to reach out to RedThread Research at [email protected] or www.redthreadresearch.com. We’d love to hear about your experiences.

Appendix 1: Research Methodology

We launched our study in Spring 2021. This report gathers and synthesizes findings from our research efforts, which include:

- A literature review of 51 articles from business, trade, and popular lit sources

- 1 roundtable with a total of 33 participants

- 15 in-depth interviews with learning leaders about their experiences and thoughts on learning content

For those looking for specific information that came out of those efforts, you’re in luck: We’ve a policy of sharing as much information as possible throughout the research process. Please see:

- Premise: “Content in the 2020s: Enabling Learning”

- Lit review: “Learning Content in the 2020s: What the Literature Says”

- Roundtable readout: “Trends in Learning Content & Content Management”

- Q&A call: "Learning Content"

Appendix 2: Contributors

Thank you so much to those of you who participated in our roundtable and interviews. We couldn’t have done this research without you! In addition to the leaders listed below, there are many others we can’t name publicly. We extend our gratitude nonetheless: You know who you are.

Angel Rodriguez

Ann Boldt

Brett Rose

Bria Dimke

Brian Richardson

Catherine Marchand

Chris Casement

Chris Olson

Clark Shah-Nelson

Eddie Garcia

Emily Crockett

Erik Soerhaug

Gordon O’Reilly

Greg Williams

Heather Bahorich

Ian Bolderstone

Jihyun Jeong

Jim Maddock

John Z.

Laurence D. Banner

Leah Holmgren

Marc Ramos

Martin Tanguay

Melissa Lamkin

Mitchel M.

Nick Halder

Nicole Leret

Robert Young

Sarah Foster

Shaun Rozyn

Stephanie Fritz

Stephen T.

Tania Tiippana

Tone Reierselmoen

Zachary Pfau

In addition, we thank Catherine Coughlin for editing the report, Jennifer Hines for graphics, Jenny Barandich for the layout, and Sana Lall-Trail for research and project management.

People Analytics Tech: Deep Dive into Employee Engagement & Experience

Posted on Tuesday, May 18th, 2021 at 1:13 PM

Introduction

In December 2020, we wrapped up our year-long study on the people analytics technology (PAT) market. One of our key findings from the study: PAT vendors responded quickly to customers’ needs that arose from the twin pandemics of 2020 (COVID-19 and racial injustice).

Practically speaking, this meant vendors focused much more heavily on employee engagement and experience than before. As Figure 1 shows, 67% of PAT vendors from our study reported employee engagement as a primary area of focus in 2020, compared to 60% a year earlier. Similarly, 58% of vendors stated employee experience as a primary area of focus in 2020, versus 43% in 2019.1 (Readers can access important details on the vendors in this space, including our assessment of them, via our interactive tool.)

Figure 1: Primary Areas of Focus for PAT Vendor Solutions—2020 vs 2019 | Source: RedThread Research, 2020.

PAT Critical to Staying in Touch with Employees

People analytics tech has enabled leaders to keep a check on employee pulse throughout the year, especially as fatigue from the pandemic began to set in. For example, 75% of employees in the U.S. reported symptoms of burnout toward the last quarter of 2020.2 Further, findings from a survey by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported 41% of American adults struggled with mental-health issues stemming from the pandemic.3

People analytics tech that focused on employee engagement and experience helped business leaders understand what was happening with their people—both with data and at scale.

For example, orgs that leveraged this tech to boost their existing (or to design new) listening strategies were better able to support their employees as they faced rapid and unexpected changes.4

Today, as COVID vaccinations roll out worldwide, a sense of hope is starting to emerge. Leaders are looking to reshape the future and redesign new ways of working. To do this effectively, they must understand how employees are feeling and how their needs are changing.

Once again, people analytics tech is poised to play a crucial role.

From measuring how employees feel about returning to offices, to making recommendations to managers on how they can communicate effectively to keep employees engaged, PAT can be pivotal in helping employers redesign their workplace strategies.

PAT Market Evolving Quickly

Given how rapidly business needs have changed, it’s no surprise that the PAT market has continued to grow and evolve in 2021. In the first 3 months of this year, we’ve witnessed some big players make important moves that reflect the growth and evolution of this market.

- Workday announced its acquisition of Peakon, an employee engagement solution

- The IPO of Qualtrics, an experience management platform

- The launch of Microsoft’s Viva, an employee experience solution

A Closer Look

The employee engagement and experience market is critical and changing rapidly, and it deserves a deeper study than we gave it in 2020. The purpose of this research is to provide those responsible for employee engagement and experience (HR leaders, people analytics practitioners and managers) with greater insights on this technology, specifically around:

- The role of people analytics in employee engagement and experience

- The different vendors in this space and how best to understand their offerings

Before we dive into the specifics, we want to take a moment to define the 2 terms “employee engagement” and “employee experience”—and how they connect to each other.

Understanding Employee Engagement & Experience

Let’s start with first clarifying the definitions for both of these terms.

Employee engagement: A measure of energy, involvement, and concentration that is exhibited in work attitudes and behaviors. It is a measure of how an employee feels and behaves at a particular point in time.

Employee experience: Employees' collective perceptions of their ongoing interactions with the org. It encapsulates the ongoing perceptions of an employee’s interactions with the org through their entire journey

Given these definitions, it is clear that employee experience has a much broader scope than employee engagement. Figure 2 below highlights a few other main differences between these 2 terms.

Figure 2: Differences Between Employee Experience & Employee Engagement | Source: RedThread Research, 2021.

So how should we understand the relationship between these 2 terms?

Employee engagement is an outcome of employee experience.

Basically, how an employee behaves is a direct result of their perceptions based on all their interactions with the org throughout their lifecycle. So, employees will be more engaged with their work if they have an overall positive experience with the org.

Figure 3: Understanding The Relationship Between Organizational Interactions, Employee Experience & Employee Engagement | Source: RedThread Research, 2021.

How Tech Can Help

Tech plays a critical role in helping orgs with both employee engagement and experience. Such solutions can:

- Offer tools for leaders to check-in and connect with their employees to improve their interactions with people

- Provide an internal platform for employees to communicate and share information to improve interactions with the overall org

- Enable orgs to listen to their employees in a continuous manner to understand how they feel

So, how has PAT leveraged these capabilities to help leaders with their challenges around employee engagement and experience? We take a closer look at this in the next section.

Employee Engagement and Experience Vendors' Capabilities

Before we venture any further, let’s define an employee engagement or experience people analytics tech vendor.

Employee engagement or experience technology vendor: A vendor that uses people data to understand employee engagement or experience.

In our 2020 people analytics study,5 we grouped all participating vendors under 9 categories, based on their tech and analysis (organizational network analysis, text analysis, workforce planning, or multisource analysis) or the talent areas they focus on (labor market analysis, learning, employee engagement and experience, employee coaching, or HCM / integrated talent management).

Employee engagement and experience was the biggest category in our study, with 36% of all vendors. PAT providers in this space offer capabilities that enable customers to do four things, as outlined in Figure 4:

Figure 4: Role Played by PAT in Employee Engagement & Experience | Source: RedThread Research, 2021.

Specific to current times, vendors have leveraged these capabilities in several ways to help their customers. Figure 5 provides details on each of the roles identified in Figure 4.

Figure 5: Roles Played by PAT Vendors to Help Customers with Employee Engagement & Experience—2020-2021| Source: RedThread Research, 2021.

Customers Are Happy with Their Engagement and Experience Vendors

Our people analytics study of 2020 included a poll of 72 customers, which revealed that customers of these PAT solutions are generally satisfied with them. Specifically, customers gave an average NPS score of 61 for employee engagement and experience vendors (see Figure 6), as compared with the average score of 67 for all vendors in the study. To put that into a bit more context, the average NPS for SaaS companies in 2020 is a score of 40,6 making 61 a great score for PAT vendors in this category.

Figure 6: Average Customer NPS Score for PAT Employee Engagement & Experience Vendors| Source: RedThread Research, 2020.

Some of the quotes from the most satisfied customers in this category include:

“An innovative vendor, constantly improving the product and providing excellent customer support and flexibility.”

Large healthcare company for an employee experience / engagement analysis solution

"Comprehensive surveying and reporting tool with good support."

Large retailer for an employee experience / engagement solution

"High flexibility can be used for multiple purposes."

Large pharmaceutical company for an employee experience / engagement solution

PAT will continue to play a crucial role in helping customers as they prepare themselves to face a new set of challenges related to employee engagement and experience in 2021 and beyond.

Employee Engagement and Experience Vendors

Let's turn to the specific employee engagement and experience vendors, which we divide into 3 categories:

- Employee engagement (EE) vendors

- Employee experience (EX) vendors

- “Passive primary” vendors

In the content that follows, for each category, we provide a framework that is based on the heritage of the vendors, such as founder or acquisition history.

The origins and backgrounds of the vendors, as well as if they’ve been acquired or have acquired others, influences the capabilities they offer and how they go to market.

Each framework provides a list of all the vendors in that category, their backgrounds, details on whether they collect perception data, passive data or both, acquisition history, and a customer NPS score, if available. At the end of each category, we provide a set of checklists to help both customers and vendors think about some key questions when selecting or selling tech (respectively).

We also provide our RedThread assessment for each vendor included in this space which can be accessed through our interactive tool. Readers can use the tool to click on the logo of a vendor and read our assessment for them.

Employee Engagement Vendors

For vendors in the employee engagement (EE) category, we created a framework with the following groups:

- Professional services background. Vendors in this group were founded by people with a strong background and experience in professional services, such as consulting. Their offerings come tightly coupled with professional services (although the tech can also be purchased on its own).

- Employee engagement native. These vendors started out as engagement survey providers, and their primary bread and butter continues to be engagement surveys.

- Employee engagement via other talent areas. Vendors in this group are known for their other products, such as performance management, along with employee engagement. A number of vendors in this group have either acquired other talent solutions in the past or have been acquired themselves—which influences their approach to the market and areas of focus.

A clear distinction among these different groups is difficult due to areas of overlap and, thus, some vendors fall into more than 1 group. All vendors included in this category:

- Have a very strong focus and background in developing employee engagement and pulse surveys

- Go to market as an employee engagement platform and have traditionally focused on engagement as a primary talent area

- Have customer success stories that primarily feature examples of understanding employee feedback and improving engagement

Figure 7 below shows our framework for this category and provides key points on each vendor. (Click on the image below to enlarge it.)

Figure 7: People Analytics Vendors That Focus on Employee Engagement | Source: RedThread Research, 2021.

Putting the framework into action

In the following checklists, we offer some key questions for potential customers and vendors to help them better understand the tech and their needs, respectively.

Real-World Threads7

Formed in 2010, Coffee Circle is a German coffee-roasting company that employs 70 people. Deborah Moschioni, Head of HR, joined the company in 2018 and introduced a people analytics tech solution that focuses on employee engagement. Her goal was to collect employee feedback so that Coffee Circle could implement initiatives that are important to the company.

When the pandemic hit in early 2020, Coffee Circle began leveraging the people analytics solution for engagement purposes to support its employees through the crisis. As Deborah explained,

“We wanted to understand how everyone was feeling during this difficult period so that any means of supporting them better could be identified. Additionally, the wording of the COVID response templates was particularly compassionate and mindful of the situations many of the respondents may be facing.”