#HRTechConf 2019: What Stood Out Amongst all the Glitz

Posted on Monday, October 7th, 2019 at 9:01 PM

This year’s HR Technology Conference in Las Vegas was optimistic and enthusiastic, brimming with talk of humanizing work, improving the employee experience, and ever-increasing vendor growth rates. If you want to see what folks thought in general, check out #hrtechconf on Twitter.

As we left the show, we captured a few of the things that struck us from the show (admittedly, we saw relatively little) and our 30+ vendor meetings:

- D&I Tech: Given that we started the D&I tech conversation a year ago at this show, we are perhaps a bit biased on this one in thinking that it is important. However, the fact that a session on this topic in the Women in Technology part of the show had hundreds of people in it (see picture above) shows the incredible interest in the topic. That said, we were extremely disappointed that the conversation did not focus on the broader D&I tech landscape of solutions, and instead was largely focused on two types of technology that serve traditional D&I needs: pay equity and harassment reporting. We wish the conversation had focused more on the opportunity of D&I tech, which is to scale awareness of D&I-related issues and provide insight during critical decision-making moments (e.g., hiring, performance feedback, promotion).

- Ecosystems and integrations: We’ve never heard as much talk about how vendors fit within the broader HR technology ecosystem as we did at this show. (Granted, Dani spent part of her session talking about learning technology ecosystems, so it was top of mind.) However, almost every vendor we spoke with talked to us about how they fit within the ecosystem of others in their space, the partnerships they are building, and the need for better and more scalable integrations. We also heard more about how vendors are being asked by customers to “figure it out” with vendors they may not have worked with in the past, putting a new pressure on partnerships and (quite frankly) flexibility among the vendors.

- Skills: The subject of skilling (or re-skilling or up-skilling) the workforce is a huge one, and we heard about it from many different vendors. There are a range of perspectives on how to measure skills and what can be done with that information (e.g., workforce planning, learning approaches, career mapping resources, internal project or job marketplaces). We are still not confident that any vendors have cracked the question of how to skill the workforce for the future, but at least folks are thinking about it.

We were asked by many vendors for advice on what they should do moving forward. Here are a few of the themes we touched on:

- Stop asking employees for information you can get somewhere else: Nearly every vendor in the expo hall is asking employees for data, many via surveys (and as we said, no matter how pretty it is, no one wants to take another survey). Yet, vendors are able to access more latent (existing) data from internal systems and external (public) sources than ever before and our technologies for analyzing that information have never been more powerful. Vendors need to break out of the habit of asking employees to give them information and instead ask: “How else can we get the information or insight we are seeking?” And then build that capability, whatever it is.

- Push more insights down to employees: Building on the previous point, we are pulling together more data and insights on employees than ever before, but it seems that the primary purpose is to give it to management to manage the business better. While that is all well and good, it is not enough, as it limits insights, decision-making, and action to management, who often serve as a bottleneck to change. Instead, organizations need to provide more information to employees so that they can better understand what is happening and adjust their work and behavior accordingly.

- Build for the future, not tomorrow: It may sound overly grandiose, but we believe we are at an inflection point in many ways with HR technology, where we are building truly revolutionary tools that will influence generations to come. To that end, we are encouraging vendors to think beyond the short-term when it comes to their product vision. For example, don’t focus just on skilling the workforce with a certain set of skills we think will be useful, but instead focus on helping organizations create environments where people are constantly encouraged to learn whatever skills are necessary. Or, as another example, identify ethical standards for people analytics – even if it may limit what can be done in the short term – so that we can set a solid foundation of trust so we can do more interesting and profound analyses in the future.

What do you think? We’d love your reactions or questions about what we’ve written and – for those of you who attended – we’d like your own reflections on your experience in the comments.

Finally, we want to thank those of you who were able to attend Dani or Stacia's sessions. Please feel free to reach out if you'd like a copy of our presentations ([email protected]).

Helping Women Rise: How Networks and Technology Can Accelerate Women’s Advancement

Posted on Monday, September 30th, 2019 at 10:24 PM

This report summarizes our findings on the role of technology in taking a network-based approach to the advancement of women.

Learn:

- The six practices organizations are using to advance women

- The current technologies that are available to support these approaches

- Ideas of how technology, in the future, may be able to add additional support

- Example case studies

- Our recommendations and advice on how to put the findings of this research into practice

Articulating Invisible Information: Leveling the Playing Field

Posted on Monday, September 30th, 2019 at 5:43 AM

In the course of our research we identified two novel approaches to advance women. This article will focus on one of the two novel approaches; articulating invisible information.

Articulating invisible information

The second novel approach we identified in this research is the concept of articulating invisible information within the organization. One of the benefits of a high-status network is that unwritten knowledge is passed around. Therefore, a key way to advance individuals not in those high-status networks is to make that unwritten information visible. Put plainly, women need to have access to information about the opportunities within an organization, so they can effectively execute them. As one executive we spoke to put it,

“It’s about being intentional – as soon as you give women the information, they're perfectly capable of being aware and knowing what to do – versus the inequitable that took place in the past.”

However, relatively few organizations made note of this in our discussions, and fewer are taking action to bubble information to the surface and take it out of the informal hallway discussions among closed networks. Perhaps the greatest challenge with this practice is that organizations may not be aware of the information shared in closed, high-powered networks – and may not even have identified the high-powered network. Without this information, it can be hard to figure out what information should be made visible.

To that end, we suggest the following activities:

- Identify critical information in high-power networks

- Identify hidden information in low-power networks

- Document all the steps – both formal and informal – in promotion processes and share that information broadly

- Take steps to ensure everyone has access to critical information

1. Identify critical information in high-power networks

As we’ve noted below, there is a lot of critical information about how to be promoted and specific career opportunities to pursue available within high-power networks. To make this information more visible, organizations need to both identify high-power networks and to determine the critical information within them.

Organizations can use ONA, offered by companies such as Humanyze, Innovisor, Polinode, and TrustSphere, to uncover some of the hidden networks and the key influencers or connectors within those networks. For example, in Figure 1, we can see a network that has been colored by gender. This visual allows us to see the less connected networks (on the edges), who are the network brokers (the single nodes connecting networks) and the centrality of other networks (how central a node is within the map).

Figure 1: Example of a network map and different silos | Source: Polinode, 2019.

Once these networks are identified, traditional solutions (e.g., surveys, quick pulse polls, focus groups) can be deployed to understand what employees know about specific factors. For example, organizations may want to know what might influence career progression such as steps for being promoted, how to build support for promotion, and how to identify and access critical development opportunities. Organizations can identify this information and then take steps to make it visible and accessible to the appropriate levels and individuals across the organization through current technologies (e.g., SharePoint sites). Another approach is to leverage some of the social networking sites (e.g., Guild, Fairygodboss, or Fishbowl, mentioned earlier) to share some of this promotion information more broadly. Finally, interventions that purposely connect people within one network to another (action learning projects, cross-functional projects, internal gig-work, matched mentorship or sponsorship) could help with the sharing of critical information.

There are plenty of other opportunities for technology to be used to make information in high-power networks visible in the future. For example, we have seen prototypes of technology that will automatically flag relevant job posts to employees, highlighting job opportunities that women may not know about from their network or based on their own research. In addition, there are some technologies (e.g., from Visier, Fuel50, and PageUp People) that highlight, given a specific position, career paths people have taken within the organization. We could foresee that technology being focused specifically for women, helping them see the paths of other women in the organization and illustrating how some of the most senior women in the organization rose. We could also see organizations opening internal blogs or videos to leaders to talk more transparently about how they were promoted and the keys to their rise (highlighting broadly previously hidden information).

2. Identify hidden information in low-power networks

Interestingly, another type of “hidden” information in organizational networks is who should be promoted or identified as a HIPO but are not because they are not members of a high-status network. There is relatively new technology available to help organizational leaders uncover this information. For example, SAP SuccessFactors’ has a feature that enables HR and leaders, during the calibration process, to identify if someone has been a high performer for a certain period of time, but not been promoted (see Figure 2). This is especially a challenge for women, because research shows they are more likely to be rated as high performers than men, but less likely to be promoted.

Figure 2: SAP SuccessFactors’ calibration flags for performance and promotion | Source: SAP SuccessFactors, 2019.

Other technologies can help identify if women are underrepresented within the HIPO pool. As shown in Figure 3, SAP SuccessFactors provides leaders with a way to compare the total representation with the representation levels in the HIPO pools. In this example of photo-less calibration, you can see the overall population is roughly 38% women, but that no women are identified as high-potential. While this may be known (and potentially appropriate) within a certain group, these technologies can make visible this type of trend across broader swaths of the enterprise. It can also provide an opportunity to re-examine the women who are deemed high-performing and understand what is preventing them from also being labeled high-potential.

Figure 3: SAP SuccessFactors’ analysis of HIPOs by gender | Source: SAP SuccessFactors, 2019.

3. Document all the steps – both formal and informal – in promotion processes and share that information broadly

Once the critical information regarding promotion processes is documented, it is important to share that information broadly so that individuals in lower-power networks can access it. Almost every organization we spoke to highlighted their use of basic technologies (e.g., Skype, SharePoint) to share at least some information about promotion or succession processes. However, the challenge is that sometimes the information is too generic or focuses too much on the formal processes instead of the information activities and behaviors necessary for promotion.

4. Take steps to ensure everyone is receiving information regularly

While this suggestion seems terribly simple, it can still make a big difference. At its essence, this suggestion is to make sure that all the appropriate individuals are being looped into emails, chats, and meetings. It is easier for someone to “forget” someone who needs a communication if they are not perceived as being in the high-power network.

In the course of our interviews, one simple hack to address this problem was shared: to make email lists (e.g., “Senior Leadership Team”) that include everyone, so that women aren’t left off the list when emails are being sent. As one woman stated,

“When the Senior Leadership Team (SLT) email list was used, I would get all the communications. If people added people by name, inevitably at least one of us women would get left off the communication.”

There are technological solutions that can help with this issue of communication equality. For example, one technology, offered by Humanyze, can show who is receiving emails or meeting notifications versus who would be expected to receive those notifications, given the group’s gender representation. For example, in Figure 4, we can see the amount of communications via email by gender. The black line indicates the representation level within the group (e.g., for Finance, approximately 50% of the team is women). However, within that Finance group, 70% of the email communications is between men. This could show that women are not being included in important email communications. This same sort of analysis can be done for meeting invitations or chat interactions.

Figure 4: Humanyze’s analysis of communication frequency by gender | Source: Humanyze, 2019.

Another technology, Worklytics, tries to address this challenge by offering email-based nudges for other people to include in a specific email or work event invitation. This technology works by generating a list of the most important work events1 in an organization (e.g., key meetings, shared documents, projects, and email threads) and then scoring each work event for diversity by looking at the relative number of differing demographic groups involved in the event. By tracking the average diversity of the organizations most important work events, Worklytics can provide a sense of the level of access to key opportunities for growth within an organization or sub-group. (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Worklytics analysis of meeting attendance, by gender | Source: Worklytics, 2019.

We’ve mentioned a lot of vendors in this section. Figure 6 summarizes those we included. Please note, a list of all vendors included in this report is in the Appendix.

Figure 6: Vendors included in articulating the invisible section | Source: RedThread Research, 2019.

How Are Companies Measuring Success in D&I Tech?

Posted on Friday, September 27th, 2019 at 8:09 PM

More and more companies are adopting software technology to help them tackle diversity and inclusion challenges. In our recent study with Mercer, we explored the emerging market for D&I technology. We looked at the challenges that were driving the adoption of technology, and we examined the landscape itself. We also evaluated the inherent risks and benefits of adoption and what companies were expecting to achieve by using D&I tech.

One other question we were curious to understand is how companies are measuring the success of their D&I software to help them achieve their goals.

Here is an excerpt from that report which looks more closely at this question, and our recommendations for companies just setting out:

When we transition to looking at the primary success measures of D&I technologies, we see slightly different success measures compared to the problems vendors are trying to solve.

Figure 1: Primary Success Measures of D&I Technologies | Source: RedThread D&I Technology Survey, 2018

While there is clear alignment between most of the problems vendors are trying to solve and the top success measures for their products, there is one anomaly: the top success measure for D&I products is employee engagement, but most D&I technology solutions are not designed to directly influence engagement.

Though decreasing unconscious bias or increasing the diversity of talent pipelines can certainly influence engagement, they are not the sole drivers of it. Establishing employee engagement as the primary measure for D&I technologies could be setting D&I tech vendors up for failure.

Further, most D&I technology vendors don’t measure engagement, so it is hard for them to prove success. We therefore suggest that vendors and customers alike reconsider the primary success metric for D&I technologies and quantify the impact it has on the specific talent area it is influencing.

Want to read more from our report on the D&I Technology landscape?

Explore our interactive tool and infographic summary and download the rest of this report, including our detailed breakdowns of D&I tech categories and solutions, and some predictions for the future of this market. Also check out our most recent summer/fall 2019 update on the D&I tech market.

Gig-work Marketplaces: A Novel Way to Advance Women

Posted on Wednesday, September 25th, 2019 at 4:44 PM

Gig-work marketplaces

During our conversations, it was often suggested that the way to advance women was to help them gain access to meaningful work in which they can collaborate with new peers and connect with diverse groups and leaders to showcase their abilities. As it turns out, there can be significant challenges to doing this both for employees within organizations and for people who are trying to rejoin the workforce. To that end, we suggest organizations consider

- Implementing internal gig-work marketplaces

- Leveraging external gig-work marketplaces

1. Implementing internal gig-work marketplaces

While some organizations have rotational programs or stretch assignments, those interventions do not tend to be broadly available or clearly communicated. Thus, many women are stuck within their existing roles without a way to meaningfully broaden their network and skill set.

To address this situation, we’d like to suggest organizations consider using internal gig-work1 marketplaces as an alternative option for women to diversify their network and to show themselves as energizers within their networks. Typically, these marketplaces are seen as part of organizations’ learning and development efforts. However, we think they could play an important role in helping to advance women as they could provide a way for women to broaden their network outside of their current team, showcase their openness to new ideas and concepts, and gain new skills through meaningful new opportunities.

What is an internal gig-work marketplace?

Gig-work marketplaces provide a place within the organization where individuals with small projects can find other employees interested in working on those projects. Therefore, anyone else in the organization who may have some extra time can potentially contribute to this work, while the person doing the work can engage with new people in a meaningful way and learn new skills. The projects are typically shorter in length and represent work that can easily be partitioned into discrete sections. The project owner interviews individuals interested in doing the work and makes the decision of who works on the project. The person wishing to do the project typically needs to get their manager’s approval to take on the additional work. The project posting process is typically enabled by technology and made centrally available.

Of course, there are potential pitfalls. For example, if organizations, leaders and individual women do not carefully consider the type of gig-work they provide and accept, it can result in a lack of substantive advantage in terms of new skills or career development and progression. Further, without planning, there is no guarantee that these projects will connect individuals to the right networks or create visibility into a woman’s capabilities. Simply having a platform or process that connects people to work doesn’t cultivate relationships and grow networks. Organizations need to create some structure to help leverage these opportunities into visibility, connection, and relationships.

Internal gig-work marketplaces tend to be enabled through technology that is available across the organization. Some of the organizations we interviewed have leveraged Sharepoint or built in-house platforms to provide a more systematic, standardized approach.

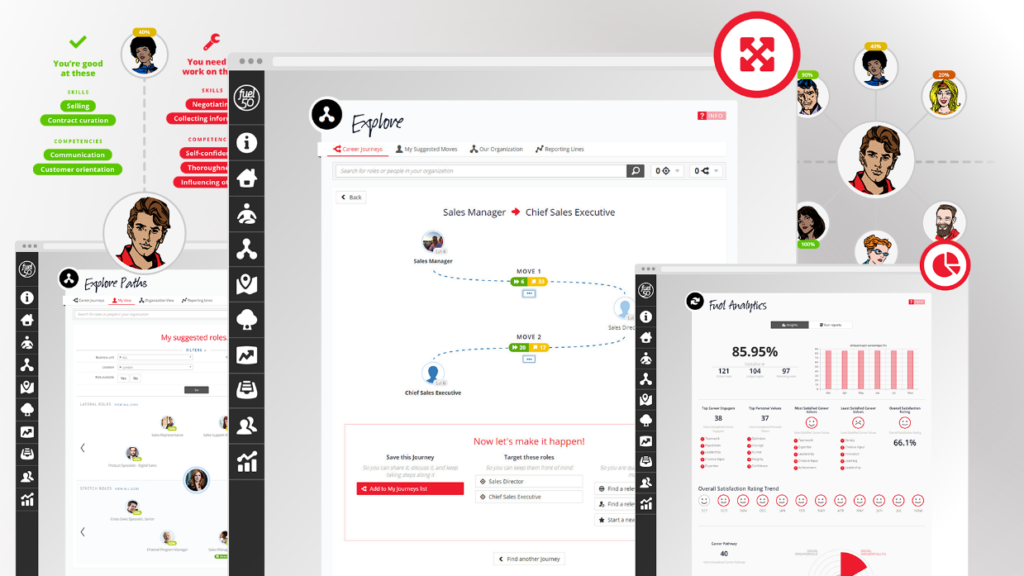

While some organizations2 create their own in-house solutions, vendors are providing solutions that help organizations build an internal gig-work platform as well. For example, Fuel50 (see Figure 1) recognizes the importance of creating a career-agile workforce. Their solution helps individuals not only identify current skill levels but also articulate what is important to them and their career. This information helps individuals and leaders identify opportunities that align with career interests, experiences, and the things that drive and energize them in their careers.

The platform suggests roles (new positions or gig opportunities), but more importantly it gives individuals visibility to all the developmental gig assignments across the organization. It also gives leaders data-based insights on their talent across the organization on real, meaningful assignments.

Figure 1: Determining career energizers and tapping into gig-work with Fuel50 | Source: Fuel50, 2019.

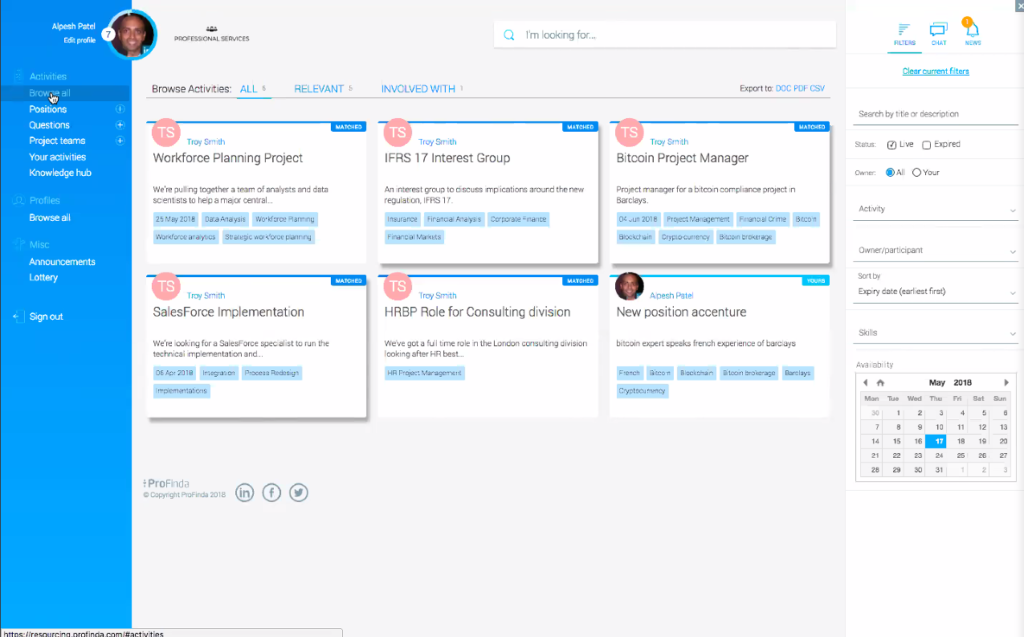

Another vendor, Profinda, takes a network-based approach in their offering and matches people to potential projects based on skills. The vendor offers an internal talent marketplace that allows people to see projects coming available and to apply for them. In addition, the solution also helps organizations identify when an individual will be available for a new assignment (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Profinda’s skill-based matching | Source: ProFinda, 2019.

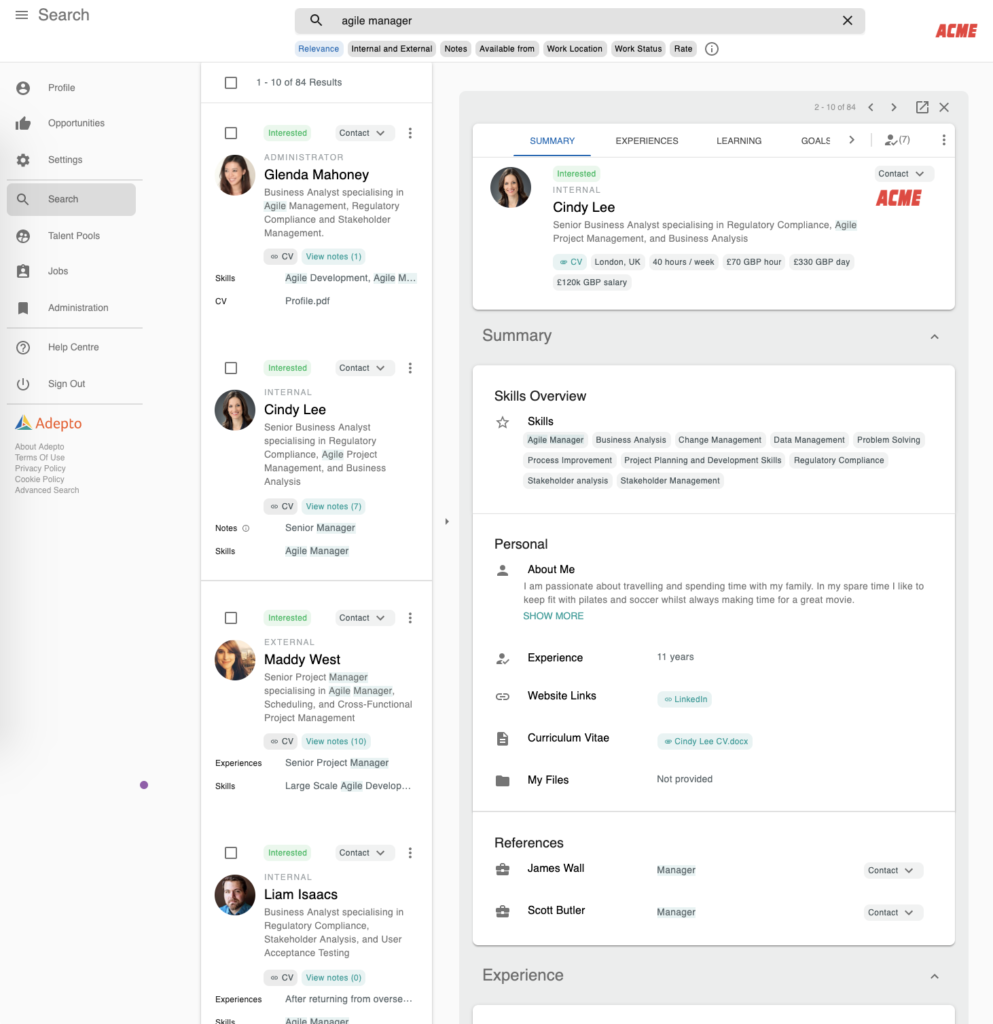

Still yet another vendor, Adepto, offers what they call a “skills based total talent platform” for a single enterprise, providing insight into “all the talent available… internal and external; past, present and future.” Users can search for individuals by skills, experiences, or qualifications, while workers build their profiles within the system, highlighting that same information and their career/skill aspirations. This type of visibility could make it easier for women to find new opportunities, and critically, make it easier for leaders to access a broader pool of talent for both full-time and project-based work (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Adepto’s search and profile interface | Source: Adepto, 2019.

This type of technology is not exclusive to new(er) players in the technology landscape. Workday has created a talent marketplace that aims to help organizations identify and develop non-traditional talent and SAP SuccessFactors has features that can be used for a similar purpose.3

In the future, organizations could look at how many women are asking for additional assignments in their development process but are not being given these or are given stretch assignments that are less meaningful than their male colleagues.

2. Leveraging external gig-work marketplaces

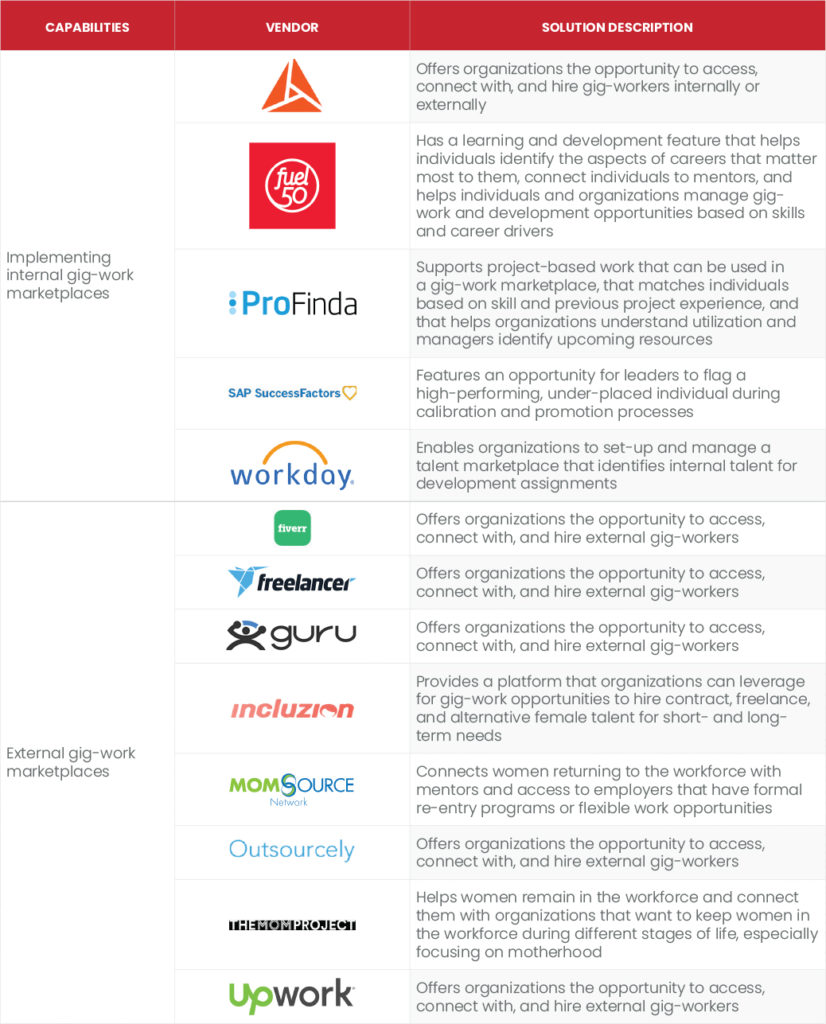

External gig-work marketplaces are much more well-known than internal gig-work marketplaces. With these, organizations can either post projects or search for workers who have the required skills, experiences, or qualifications. Some of the more well-known gig-work platforms include Upwork, Fiverr, Guru, Freelancer.com, and Outsourcely.com.4

There is increasingly a niche for diversity-related gig-work platforms. With these platforms, women (or other diverse individuals) can identify organizations that are prioritizing diversity, find projects that are of interest, meet individuals who could be interested in helping them move into the organization, and show their skills and capabilities. In particular, this type of technology could be leveraged for women who are returning to the workforce after an extended break or who have challenges with finding the right organization or network to get started again. This technology can also connect organizations to a diverse talent pool that they would not have been able to purposefully access in the past.

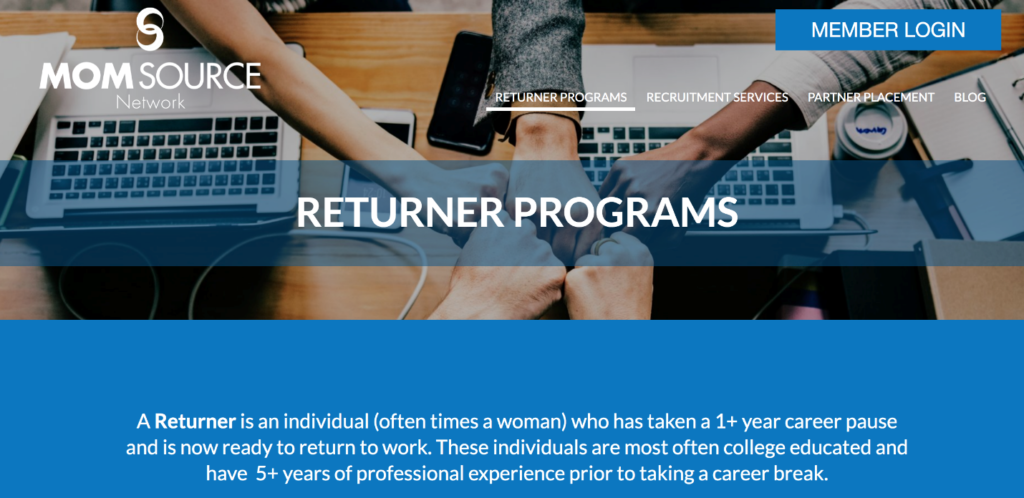

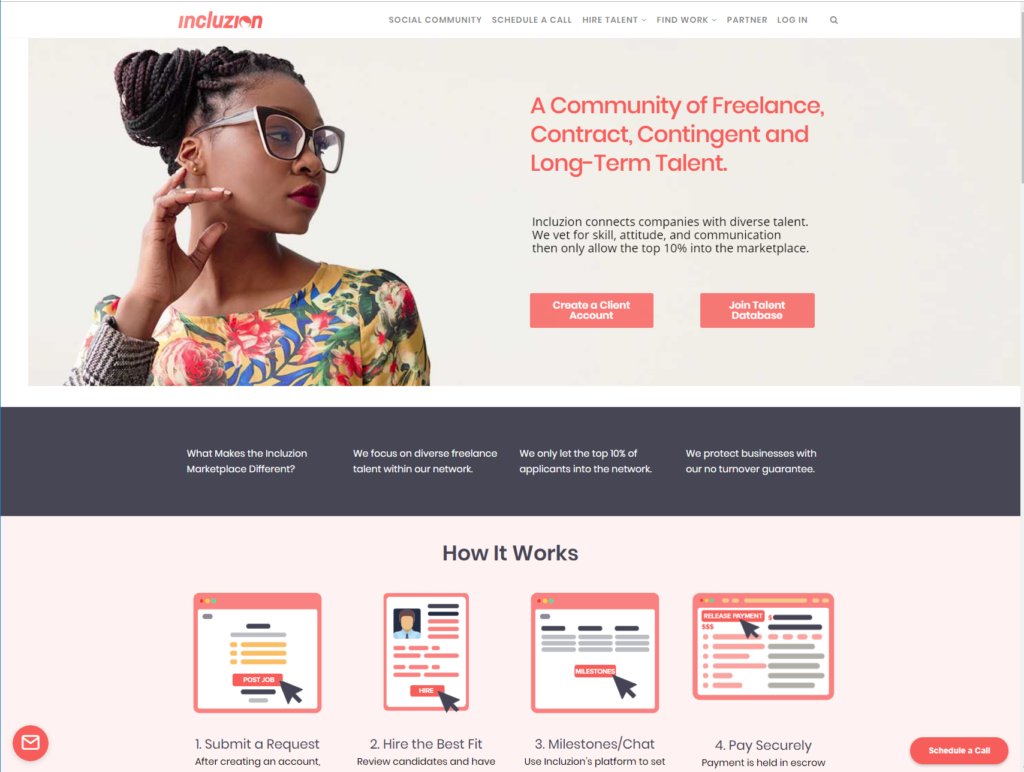

There are a range of tools available on the market. For example, Mom Source Network and The Mom Project are both working to develop deep talent pools that organizations can tap into. Mom Source Network specifically offers resources as well as access to job postings to people who are returning to work from an extended break (see Figure 4). The Mom Project creates Maternityships®5 which are time-bound opportunities for new talent (likely another woman who is trying to connect with the organization and gain meaningful skills) to fill a role in the organization while another woman is out on maternity leave. Incluzion.co is another gig-work marketplace, but they focus across all diversity characteristics (see Figure 5). All these solutions are designed to help diverse talent gain new skills and experiences while expanding their network and showcasing their abilities.

Figure 4: Screenshot from Mom Source Network | Source: Mom Source Network, 2019.

Figure 5: Incluzion.co’s gig-work marketplace | Source: Incluzion.co website, 2019.

We’ve mentioned a lot of vendors in this section. Figure 6 summarizes those we included.

Figure 6: Vendors included in the gig-work marketplace section | Source: RedThread Research, 2019.

Leadership Programs and Conferences: Building Networks for Women

Posted on Wednesday, September 18th, 2019 at 11:00 PM

Leadership development programs

There is significant variety1 in the types of leadership development programs designed to help women advance, including programs that have the following characteristics:

- Focus on women and have only female participants

- Open to everyone, with no gender focus, but participants are selected in such a way as to have equal representation among men and women

- Open to everyone, with no gender focus and no requirement around equal representation

In addition, the ways in which women access these opportunities differs. Some organizations have a process for women seeking out and applying for these programs, while others are based on women being identified as top talent and invited to participate. Still other organizations hold leaders accountable for sponsoring women participants by pushing leaders to seek out top talent, to nominate them for selection, to form relationships with them, and to take responsibility for their development throughout and after the program.

We mention these different varieties of programs because the program type and how women access programs can have significant impacts on the networks women build as a result of the program. To make the most of these programs, we suggest organizations do the following:

- Design programs to intentionally build women’s networks

- Create earlier-career programs for women

- Go beyond traditional approaches to identify program participants

- Teach network theory

1. Design programs to intentionally build women’s networks

Leadership development programs can often have the same pitfalls as women-focused ERGs. Specifically, if program participants are from similar functions, units, or levels, these programs can create echo chambers and restrict women from access to information, visibility, and opportunities to display their talent across the organization.

When these programs are designed to provide visibility, opportunity, and experience, they can enhance a woman’s ability to showcase her talent, to collaborate, and to be seen as an energizer among peers. In addition, when organizations are intentional about how they design these programs – specifically ensuring equal gender representation and opportunities for women to forge meaningful connections with other women – they can enable the creation of inner circles for women without being exclusive to women.

Fixing the woman vs. Fixing the workplace

The initiatives that organizations implement to enable the advancement of women tend to rest on one of two basic beliefs that either:

- The women need to be fixed or

- The organizational culture, practices, and policies need to change

Organizations may undermine their efforts when they position development as women needing to be fixed. For example, when leadership development programs focus on “business skills for women” or how to “dress for success,” they can be patronizing and discouraging, sending the message that women need to fix themselves or portray themselves in a certain manner.

Organizations can no longer operate from the perspective that women need to be fixed. Not only is this an erroneous conclusion, but organizational policies and practices created in different times have supported cultures in which men have disproportionately benefited. That simply won’t work as the demographics, desires, career interests, and expectations of employees change. As one executive put it,

“Quite often there are assumptions made . Careers are going to change, things are going to be fluid, and workplaces will change. People are trying to give advice on how things have been and that is going to change. The future will not look like the past.”

This point underscores the need for organizations to create environments where women can succeed as opposed to always expecting women to adapt and then being surprised when women are not rising within the organization. If organizations keep trying the same approach, they will keep getting the same result.

2. Create earlier-career programs for women

Many leadership development programs focus on senior-level women or those moving into senior roles. This can be problematic in that, by this point, the pipeline of female talent has already significantly reduced so the impact of the programs is muted. Even when these programs are offered to women in lower levels, they tend to be limited in scale and focused on a small subset of women.

This problem of focusing too late in women’s careers can be magnified when you think about it from a network perspective. Specifically, if women’s primary relationships are with other women at their same level or of a similar age, then the examples they are seeing of how to manage challenges are largely homogenous. One area this may play out, especially for women, is in navigating home and work lives.

A majority of the family responsibilities still fall on women. Therefore, they are more often than men faced with the dilemma of balancing career progression while also “holding down the home front”. Without diverse connections to women across the spectrum of career tenure, talented women who may be struggling with the question of whether to or how to leave the workforce or reduce their workload may end up being surrounded by other women struggling with the same question. These women would benefit from access to diverse perspectives, advice, and resources so they could come to conclusions best suited for their situation. If organizations develop leadership programs that also connect women to others who have grappled with this question, they may be more effective at keeping some of these talented women at their organization or increase the likelihood they will return after taking time away.

3. Go beyond traditional approaches to identify program participants

As alluded to earlier, one of the challenges with many leadership development programs is that they require a senior leader to nominate people to participate. While this may sound good in theory, it requires nominees to already have a network that connected them to senior leaders who know them well enough to make the nomination and a manager or network that connected them to the right opportunities to be eligible. Given what we know about how networks vary by gender, we know this is less likely to happen for women.

There are several ways to address this. The first is to make explicit the existence of the program, the requirements for accessing it, and information on how to be prepared to successfully leverage it (this is similar to what we discuss in more detail later in the “articulating invisible information” section). It is critical to make this information widely available so that anyone can find it. A typical place to locate information about a leadership program is within a company’s intranet site.

However, given the proliferation of business-specific social networking sites, which claim to offer “real” insight into how work happens at companies, it may be worth considering sharing this type of information in one of these alternative formats. While making this information broadly available may give you a moment of pause, consider the potential benefits to your employer brand: organizations can clearly explain how they invest in women and what they expect people to do to advance.

Some of the more obvious business-specific social networking sites to share this on include LinkedIn and Glassdoor, but other sites such as Fairygodboss or Fishbowl could represent new opportunities to share information about leadership opportunities where people are already talking about them. These sites are designed toward sharing “unvarnished” advice. For example, on Fishbowl, individuals can direct questions to others in their organization about any topic – like mistakes younger professionals make or the value of an MBA (see Figure 1) or how one accesses leadership opportunities. Women focused communities can also use Fishbowl to ask questions of other women in the group (also see Figure 1). Further, C-suite leaders can host Q&A sessions on a range of topics, for either individuals only within their organization or for anyone in the industry.2 Finally, Fishbowl also has formal partnerships with a variety of professional organizations such as Time's Up, which provides a safe space for women in a variety of industries, and The 3% Movement, which pushes forward pay equity.3 These specific communities could be excellent new sources of talent for an organization and an appropriate place to share details about how an organization supports and develops women.

Figure 1: Example of dialogue in women-focused groups and "coaching and mentoring at scale" | Source: Fishbowl, 2019.

While sharing information broadly may increase the supply of leadership program participants, it is not the only approach to doing this. New technologies are enabling organizations to identify different leadership development or high-potential (HIPO) program participants. For example, TrustSphere, an ONA provider, believes that HIPOs tend to have more network connections – but those connections may not be part of the network of folks who could nominate them for a HIPO program. To that end, TrustSphere offers a technology that will allow organizations to identify “hidden stars,”4 (see Figure 2) who potentially should be included in HIPO programs based on overall numbers of network connections (see company spotlight below). This could be a way to highlight overlooked female talent. In our full report, due out in October, we describe how Ramco Systems uses ONA to identify HIPO trainees.

Figure 2: TrustSphere’s approach to identifying “hidden stars” | Source: TrustSphere, 2019.

4. Teach network theory

Finally, and this may sound somewhat obvious, organizations should consider teaching women about network theory and the impact it can have on their professional advancement. Despite the obviousness of this fact, we found very few organizations actively teaching their leaders about network theory. In our full report, due out in October, we describe how Unilever is an exception to this rule.

Beyond teaching about network theory, organizations can use technology to provide tools and resources for leaders and employees – women in particular – to conduct an audit of their networks. Organizational network analysis (ONA) is the primary tool we see applied here. This knowledge is helpful when planning out more formalized activities because programs can be created to specifically address any disparities in networks that result in different outcomes between men and women. In addition, this information can be used in trainings to highlight the impact of networks on the advancement of women and can help individuals see how behaviors reinforce and shape their network (see company spotlight, below).

There are a number of different vendors that can help organizations do this analysis. For example, TrustSphere uses ONA5 to help organizations and individuals gain a better understanding of how relationship networks are operating in real time (see company spotlight, in the full report, due out in October). Innovisor, another ONA vendor, helps organizations uncover hidden gender issues in their organization such as how often and to whom different groups of individuals collaborate.

We’ve mentioned a lot of vendors in this section. Figure 3 summarizes those we included.

Figure 3: Vendors included in leadership development section | Source: RedThread Research, 2019.

Conference attendance

Most companies indicated that supporting conference attendance is the primary way women are encouraged to build external networks. Specifically, conferences were cited as a mechanism to

- Help individuals gain knowledge and insight

- Ensure individuals stay on top of current thinking and skills

- Connect individuals to a larger network

Obviously, for the sake of this report, the latter point is of greatest interest. While conferences are great tools to provide employees with information, there is no guarantee that the connections someone makes at a conference will aid in development and/or career advancement. Simply put – conferences increase the potential opportunity for making the “right” connection, but that’s typically by luck of the draw, not by design or intent.

Organizations and women may get more from conferences when they are armed with information on why and how to intentionally develop a network, what steps to take in advance of an event, and how to extend their connections beyond the conference. To help women get the most from conferences from a network-based perspective, we suggest that organizations do the following:

- Provide guidance on before-event activities

- Create follow-up opportunities

1. Provide guidance on before-event activities

Many people think that conferences start when they show up on the first day and therefore, fail to complete the preparation necessary to connect with the right people at the event. Organizations may want to consider offering bite-sized resources (e.g., one-pagers or 3-minute videos) to employees on how to get the most of events before they even arrive. For example, these resources could cover:

- Identifying speakers in advance of the event and asking to share a coffee or lunch

- Posting on social media that they will be attending the event and asking if others will be as well and are interested in meeting up

- Connecting with conference organizers to see if there are any small volunteer opportunities to:

- Create and grow a community of attendees on social media before the event

- Help in a small way at the event to meet specific new people

All these suggestions can give women opportunities to diversify their networks and to energize their networks through their openness to new people and experiences.

We think there’s also an opportunity here for conference organizers and app developers to make technology that can be used to build better networks. For example, before people attend conferences, an app could be used to provide nudges for people that they should meet at the event, based on similar geographies or titles (or potentially interests, which could be identified via LinkedIn profiles or through people’s selection of interests). Further, technology could match people to others who are in the same sessions (based on location services) and who have similar interests.

2. Create follow-up opportunities

No matter how amazing the event, if people do not follow up on those new relationships after the event, they lose a significant opportunity to strengthen their external network. To that end, organizations could create expectations for how women will engage with the individuals they meet at conferences. Again, this could include creating bite-sized learning; sharing ideas for how to build and sustain that external network. Some ideas for what women could do post-conference include

- Forming social media groups or in-person meet-ups for conference attendees to stay connected

- Following up with speakers via online social networks to learn more about their sessions

- Writing about their experience (internal or external blog or on social media) and inviting others to share their reflections or engage in additional dialogue

To date, we have not seen technology that focuses in this space. However, we think there is an opportunity for post-conference technology that can continually nudge and reinforce what was learned and presented at the conference. For example, conference apps could send a nudge reminding the individual to reconnect with someone they met at the conference and share how they have put their insights into action. The technology could send out reminders of key ideas from sessions the individual attended and ask what else they might want to know more about. Development opportunities, based on sessions attended or career interests, could be pushed to the individual throughout the year (other conferences, online courses, books, etc.).

Women & Networks: Mentorship & Sponsorship – Building Broader Networks

Posted on Tuesday, September 10th, 2019 at 3:28 PM

Mentorship and sponsorship1

It is no secret that mentorship2 and sponsorship3 can help advance women.4 Despite this insight, there is a high degree of variance in the extent to which mentorship and sponsorship are formally developed and implemented5 across organizations. For example, many organizations simply “encourage” mentorship or sponsorship but have not formalized the program nor offered resources. By contrast, at IBM, any employee who is willing to share their knowledge can sign up to become a mentor or coach. The company even built its own platform, CoachMe, to increase the reach of mentoring opportunities throughout the organization.

This inconsistency in approach means that there is also inconsistency in the effectiveness of mentorship and sponsorship geared toward advancing women. Research by McKinsey & Co. shows that when mentorship and sponsorship activities are left to take place organically, women will get less mentorship and sponsorship than men, as indicated in Figure 1.6

Figure 1: Those who have never had substantive interactions with senior leaders, by gender | Source: McKinsey & Co, 2018.

Research also shows that as women rise in organizations, this trend only accelerates.7 This leaves us to conclude that simply encouraging women to have a mentor, encouraging her to attend a networking event, or connecting her to a high-powered individual is not enough. There needs to be a formalized and supported mentorship and sponsorship program.

When we further look at mentorship and sponsorship through a network lens, another challenge becomes clear: the way most programs are set up today creates single points of contact into higher-power networks. This can be problematic because they are also single sources of failure since mentees or sponsorees must rely on their mentor/sponsor for support or sponsorship into the network. Further, mentors or sponsors may end up having more mentees or sponsorees than they have time to adequately support.

Beyond formalizing mentorship and sponsorship programs,8 companies can focus on ways that mentorship and sponsorship can work from a network perspective for advancing women. Specifically, organizations can focus on the following:

- View mentorship and sponsorship in terms of teams, not just one-on-one relationships

- Create energizer opportunities within mentorship/sponsorship interactions

- Connect women to diverse external mentorship/sponsorship networks

1. View mentorship and sponsorship in terms of teams, not just one-on-one relationships

One way to make mentorship and sponsorship work more effectively is to design the program in a way that it can help women form a meaningful inner circle with women from diverse backgrounds. The most important component of this is to move beyond seeing mentorship and sponsorship as strictly one-on-one relationships and instead, view mentors and sponsors as teams or cohorts. In Figure 2, we have outlined how this could work, where the team meets at times as a larger group, sometimes with one mentor and two mentees and in other instances with just the mentees.

Figure 2: Suggestions for how to take a team-based approach to mentorship/sponsorship | Source: RedThread Research, 2019.

The potential benefits of a team-based approach9 are significant, in that it can:

- Provide more opportunities for women to form an inner circle with other women who are connected to diverse networks.

- Reduce the burden on any one mentor/ sponsor since there would be more individuals to provide advice, support, or sponsorship.

- Create an opportunity for mentees/sponsors to be connected into higher-value networks through more than one individual.

- Enable multiple people to be involved in the mentorship/sponsorship relationship, reducing hesitancy some senior men feel about mentoring/sponsoring women10

One of the most difficult parts about a mentorship/sponsorship program is the logistics of matching and managing the relationships. However, there are a number of technologies that can help alleviate these logistical burdens. Further, current technology helps ensure that women are not hampered by their network and allows them to search for mentors and coaches (internally and externally). For example, Chronus (see Figure 3) offers search capabilities and mentor matching features. In addition to connecting people to mentors in their network, another vendor, InstaViser, integrates productivity technology into an organization’s current work (e.g., Microsoft Office or G-Suite) and helps individuals schedule and manage their interactions with their mentors/sponsors.

Figure 3: Mentor search and matching features in Chronus | Source: Chronus, 2019.

To date, we have not seen technology that focuses on how to match teams of mentors/sponsors to mentees/sponsorees, but we imagine that some of the existing technology could be adapted relatively easily to this case.

The #MeToo backlash

While organizations are trying to include men in the discussion of and efforts around gender diversity, some men are hesitant to get involved. Recent research11 shows that 60% of men now feel uncomfortable being involved in a common work activity with a woman. In addition, senior-level men are far more hesitant to interact with junior women than junior men out of a concern over how it might look.

Organizations need men to step up and commit to being part of the solution. Men, particularly leaders, need to be held accountable for how equitable they are in their mentorship and sponsorship activities. Male leaders should also be expected to get involved in gender diversity discussions, programs, and groups throughout the organization.

For men who have concerns about mentoring or sponsoring women in a 1:1 environment, organizations could support some form of group mentoring or sponsorship, similar to that described at the University of Michigan Department of Surgery. This approach would have the additional benefit of helping connect women to multiple leaders, reducing the reliance on a single connection to a higher-powered network.

2. Create energizer opportunities within mentorship/sponsorship

It’s important to structure mentorship / sponsorship relationships in ways that can allow women to serve as energizers within their networks. This is potentially easiest if organizations adopt the team-based mentorship / sponsorship approach. This would provide women with a safe group of individuals to try out new ideas. This would allow mentees / sponsorees an opportunity to hone their effectiveness at being energizers within their networks.

That said, an organization does not have to adopt a team-based approach to mentorship / sponsorship to introduce the concept of energizers into their mentorship / sponsorship practices. Even with one-on-one relationships, mentors / sponsors could promote their mentees / sponsored within their network as people who are good sounding boards for new ideas. This would give the mentees/sponsored both chances to be energizers and to develop more diverse ties.

To be clear, we did not see any organizations deliberately taking this approach. However, given the existing research, we think it holds a lot of potential, and we encourage organizations to incorporate it.

3. Deliberately connect women to diverse external mentorship / sponsorship networks

Women should not limit their diverse ties or energizer status to inside their organization. While it may seem odd that organizational leaders would support women developing their external network, consider this: research on innovation and agility underscores the importance of individuals having strong external sources of information (i.e., networks) outside of their organization.12 Strong external networks may eventually benefit women in terms of external advancement; in the meantime, these connections can benefit the organization in terms of new ideas and potentially new talent.

There are a number of technology solutions currently available to help with connecting women to mentorship/sponsorship networks. For example, Guild offers networking and mentorship capabilities within the organization and in communities external to the organization (Figure 4).13

Figure 4: Example of networking opportunities on Guild | Source: Guild, 2019.

Another vendor, Fairygodboss, provides an external social network for women to connect with others to better understand companies that are supportive of women and to ask the network for help in finding new roles or advice on advancing in their careers14 (see Figure 5). In the future, Fairygodboss is planning to launch company-specific communities, which could be used to help find internal mentors/sponsors or uncover invisible information (which we discuss in much greater detail later in this report).

Figure 5: Developing and leveraging an external network with Fairygodboss | Source: Fairygodboss, 2019.

Lastly, mentoring and sponsorship are personalized forms of development. To that end, mentorships and sponsorship programs alike can leverage technology that helps identify and offer personalized career pathing and development. For example, Landit offers a personalized career pathing experience with executive coaching, targeted skill development, personal branding and more. The platform’s board of advisors tool provides guidance and structure on how to manage mentor and sponsor relationships. This can be used in the mentorship or sponsorship relationship to add structure to what tends to be a less formalized practice. Another vendor, Everwise, provides not only a mentoring solution but also a marketplace of development content and curriculum across a number of topics.

We think there’s a significant opportunity for technology to help with mentorship and sponsorship in the future. For example, we could see technology enabling individuals to do the following things:

- Automate agendas for check-ins

- Send pulse surveys about current challenges

- Connect teams of mentees/sponsored with mentors/sponsors

- Provide curated content and curriculum

We’ve mentioned a lot of vendors in this section. Figure 6 summarizes those we included. Please note, a list of all vendors included in this report is in the Appendix.

Figure 6: Vendors included in the mentorship/sponsorship section | Source: RedThread Research, 2019.

Women & Networks: Employee Resource Groups – Taking A Networked Perspective

Posted on Wednesday, September 4th, 2019 at 2:26 AM

ERGs for women are incredibly popular, despite some of the debate around their utility.1 The initial idea, which was to create a shared space for women,2 has morphed in some organizations into a focus on gender as an inclusive category. However, regardless of the focus of these ERGS, almost every organization we spoke to indicated difficulty in appropriately and effectively including men in the ERG (see our callout, “The role of men in ERGs,” for more information).

Given our understanding of how networks work and how they differ by gender, the women-majority composition of women-focused ERGs can create some real challenges when using these groups to help women advance. For example, if the individuals within an ERG are primarily lower-level employees, these groups are less likely to play a large role in helping women make the connections necessary to rise within their organizations. Further, if the activities within the ERG do not enable members to form meaningful connections, those activities could take up time that individuals could spend on higher-value projects or on other activities that form those connections.

That said, ERGs have great potential to help women advance if designed, executed, and supported appropriately. In fact, if they have the right components, we think that they can be one of the most powerful network-related levers for helping women advance. We’ve summarized the most critical components, highlighting how they intersect with the four foundational principles, and listed them here:

- Create personal, meaningful sub-groups that provide leadership opportunities

- Encourage and manage toward a diverse ERG

- Offer resources to support women becoming energizers

1. Create personal, meaningful sub-groups that provide leadership opportunities

ERGs can provide women with an opportunity to be central within a network, which can be especially important for women who are not able to do this (for whatever reason) in their day job. To enable this, ERGs need to offer a wide range of meaningful leadership opportunities that allow women to build a strong network with other ERG members. At the same time, ERGs need to enable women to develop a strong inner circle of women (this is an area where ERGs have traditionally shone, given their large composition of women). It’s critical to make sure that the leadership opportunities and the connections are meaningful.

There are many ways to do this such as creating subgroups or subcommittees focused on specific topics of interest or concern to the ERG, which provide women with opportunities to take on various leadership roles. In some organizations, these groups are subcommittees of the larger ERG leadership structure.

One of the more novel types of subgroups are Lean-In Circles, which are small, intimate, member-driven groups (usually 8 – 12 individuals) that meet regularly to offer mentorship and advice to navigate roles and careers and engage in shared learning and development. These circles can allow women to both serve as leaders (network centrality) and build a strong inner circle of women. Leanin.org offers technology to help Circle leaders and participants manage their Circles and engage in meaningful activities (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Screenshot of a Lean-In Circle | Source: LeanIn.org, 2019.

Lean-In Circles are clearly not the only way to create these meaningful connections, though. Other smaller types of groups we’ve heard about over the years include corporate book clubs (small groups coming together to discuss career-relevant books and their implications), peer-mentorship groups (small groups coming together to support each other with advice), and group mentorship (small groups coming together to support each other, but with one or more senior individuals who provide the group with guidance). Note that these groups can be offered to both genders while Lean-In Circles are primarily focused on women.

The role of men in ERGs

Unfortunately, only one in five women and one in three men say that the men in their company regularly participate in initiatives to improve gender diversity.3 The inclusion of men as allies or partners in the advancement of women was frequently brought up in our discussions. Organizations cited both practical and philosophical reasons for including men in these efforts. In addition, the mechanisms that are used to encourage and maintain the involvement of male peers differs across organizations. Moving forward, organizations need to see the involvement of men as a critical component to an inclusive workforce and need to explicitly understand how and when they will involve men in ERGs, recognizing that it is not an either/or proposition.

All of these groups and subgroups point to the need to manage the logistics and membership of ERGs. Some organizations, particularly those that are smaller and less organized, have used SharePoint or social media groups (e.g., Facebook for Work or LinkedIn) for ERGs to stay connected and share information.

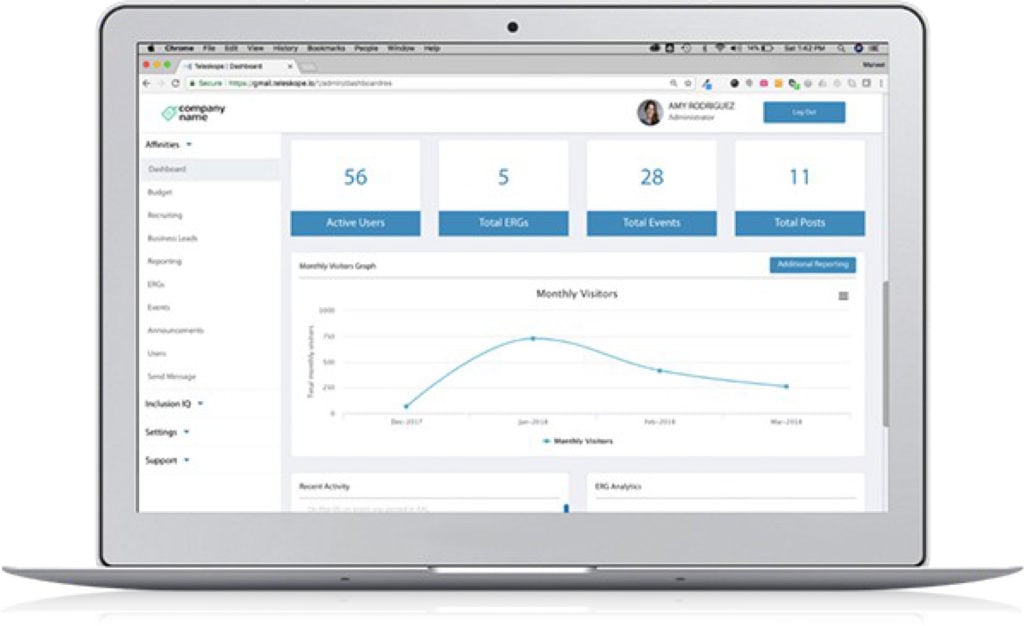

In addition, there are several different types of technologies that are designed specifically to manage ERGs, which can be useful for making these groups more efficient and effective. Some of the vendors in this space include Affirmity, Diverst, Planbox, and Stratus TMS. For example, Stratus TMS’s ERG Insights product allows individuals to manage events, action plans and budgets, and incorporates measurement tools that track ERG performance and impact (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Stratus TMS’s ERG Insights Management Capabilities | Source: Stratus TMS, 2019.

2. Encourage and manage toward a diverse ERG

As odd as it may seem to say it (given the topic), we are going to: ERGs need to have a diversity of individuals within them. This means they are comprised of individuals who are diverse on multiple levels, including gender, experience, level and location in the organization as well as the other traditional diversity characteristics. This allows women to build diverse networks, which will connect them to both higher-power and lower-power networks across the organization.

Beyond recruiting individuals from throughout the organization, how can an organization make its ERGs diverse? This challenge actually represents a prime opportunity to leverage technology. There are several ways technology can help organizations understand and increase the diversity of their women-focused ERGs. In the simplest approach, organizations could run analyses of the representation of members of existing ERGs, looking at the diversity of levels, functions, tenure, and genders. For example, this analysis might show a strong representation within the ERG from a specific function (e.g., sales), but much weaker representation from another (e.g., operations). Leaders could then actively recruit new individuals from less represented areas to the ERG to ensure everyone has an opportunity to build a diverse network.

As mentioned above, technology vendors such as Affirmity, Planbox, Stratus TMS, and Diverst help organizations track ERG members (as well as manage the logistics of ERGs). This information could then be combined with existing HRIS data to understand more about who is within the ERG. Some vendors, such as Affirmity (Figure 3), can actually do both the ERG management and representation analysis within one system. The majority of organizations, though, will likely have to combine data from multiple sources, working closely with their people analytics teams.

Figure 3: Affirmity’s ERG management capability | Source: Source: Affirmity, 2019.

Another, more sophisticated, way to use technology to understand the diversity of the individuals – and their networks – within an ERG would be to run a passive or active organizational network analysis (ONA)4 of ERG members. This would allow D&I or ERG leaders to analyze the connectedness of the ERG membership and to identify individuals who could be better connected within the network or those who could take a lead role on bringing more disparate parts of the network together.

There are numerous ONA companies on the market right now, but a few that are specifically focused on using ONA to benefit D&I are Humanyze, Innovisor, Polinode, TrustSphere, and Worklytics (all of which we will discuss in more detail in the sections to come). In the example in Figure 4, you can see how one group is highly fragmented, with the specific connectors being marked in red circles. ONA technology allows organizations to run a simulation of bringing the right people together to increase connectedness and information flow. This type of analysis could be used to help create a more diverse ERG.

Figure 4: Example of a fragmented and potentially more cohesive network map | Source: Innovisor, 2019.

As the world of people analytics continues to advance, organizations will have an ever-increasing amount of data on their hands, which could enable a range of technology capabilities that could help with making ERGs more diverse. For example, in the future, organizations could identify people who are connected to a population relatively under-represented within an ERG and “nudge” them to recruit individuals to the ERG. For example, imagine an ERG is largely comprised of salespeople, and one of the salespeople just moved into marketing. The technology could then nudge that person to invite some of the marketers to the ERG.

Organizations could also recommend different ERG groups and or events to employees based on employee data and/or engagement data. For example, if employee data suggests that a particular talent segment (e.g., women at certain levels/tenures/functions) are less engaged, have lower satisfaction or commitment, or report less development opportunities, the organization could send communications suggesting specific ERG-related activities that might be of interest.

3. Offer resources to support women becoming energizers

The final area of opportunity for ERGs is within the “energizer” principle, where women serve as energizers within their networks, helping encourage new ideas. If organizations take some of the steps mentioned above – creating clear leadership opportunities and smaller subgroups – there are numerous opportunities for women to serve as energizers.

One common approach to enabling women to serve as energizers is through ERG-enabled mentorship and sponsorship activities. In fact, mentorship and sponsorship are so important that we have an entire section devoted to them below. However, we did find this nice example from McGraw-Hill on this topic, so we want to share it here.5

One of the most powerful ways we’ve seen organizations use ERGs is by enabling their members to leverage the specific insights of their community to help deliver a better product or service. A common example of this is Dorito’s Hispanic ERG developing the guacamole Dorito chip, which added significantly to PepsiCo’s bottom line.6 Leaders who champion these efforts within the ERG can take on central roles that expose them to a breadth of individuals and ideas, thus representing a prime opportunity for women to be energizers within their networks.

However, not everyone (man or woman) is born knowing how to help nurture new ideas – in fact, some of us seem to come out of the womb as natural critics. ERGs represent a wonderful space for learning how to develop new ideas and innovations, which can be especially helpful in enabling women to be energizers within their networks. Providing resources that help women understand the steps in an ideation process – how to brainstorm and effectively support ideas without overly criticizing them in their infantile stage – could be helpful. This type of support could come in the form of the approaches many ERGs use today: discussion forms, workshops, training, and job aids.

This is also a space where technology could help. There are some new vendors focused on trying to develop and encourage ideation and innovation. Two of them in particular, Balloonr and Planbox, are specifically designed with diversity and inclusion in mind. These vendors allow individuals to conduct online sessions to generate and manage new ideas (see Figure 5 and Figure 6). Employees can use these technologies to anonymously provide ideas and respond to other’s suggestions. This helps prevent bias against specific ideas based on who provided them. Both technologies could be leveraged in the context of ERGs to not only harness the collective insights of the group but also give women opportunities to lead and serve as idea-encouraging energizers within their networks.

Figure 5: Balloonr’s idea generation platform | Source: Balloonr, 2019.

Figure 6: Planbox Screenshot | Source: Planbox, 2019.

We’ve mentioned a lot of vendors in this section. Figure 7 summarizes those we included. Please note, a list of all vendors included in this report is in the Appendix.

Figure 7: Vendors included in ERG section

Networks and Gender: Why Do We Care?

Posted on Thursday, August 29th, 2019 at 4:20 PM

Efforts to improve women’s representation in leadership are decades old, yet the numbers remain stubbornly low:

- For every 100 men promoted, only 79 women are promoted1.

- Approximately 40% of women in senior roles/technical positions report being one of the only women in the room2.

- The World Economic Forum3 estimates it will take 168 years for North America to close the global gender gap.

So, why don’t we see more women in leadership?

There are many potential answers to the question of why women do not rise at equal rates as men. However, of all the potential solutions, our research identified one we think deserves more attention than it has received to date: women are not gaining access to the information and opportunities they need from their professional networks in order to advance.

Our network connects us to the right groups, people, and information and inclusion at work – through our networks – can be a critical factor that influences promotion and advancement opportunities. Unfortunately, research indicates 81% of women report some form of exclusion at work, yet 92% of men don’t believe that they are excluding women at all4. This difference highlights the critical, yet less obvious influence of our professional networks.

Based on our interviews, women tend to advance when three conditions are present:

- People work with them and experience them as equally competent professionals.

- They are given access to opportunities and experience.

- They are included in conversations and have access to information at the right level.

Focusing on networks can help with all these things. More specifically, networks – and the information they carry – are one of the primary ways people learn about career advancement and development opportunities. By being in the right networks, women have an opportunity to work alongside and for others who would support them in their advancement. They also have access to high-quality opportunities and can have the conversations that help them advance.

However, research suggests that women and men's networks – and the information within them – are different. Understanding these connections between people – who knows whom and why – could help organizations understand why some employees rise and why others do not.

How are men and women’s networks different and why does it matter?

Traditional social dynamics – along with promotion rates, power, and rank – influence the creation and composition of professional networks.5,6 In general, as men move up the ranks in organizations, they join higher-status networks with more information and power. They also are more likely to be surrounded by men, because men, statistically speaking, are more likely to be promoted. Women – who tend to be promoted at lower rates – more often find themselves in lower-status networks (which can be women-dominated).

Network status influences the extent to which someone has access to key conversations, information, and projects that would help them advance in an organization.7 Since men tend to be in those high-status networks, they tend to have access to higher-quality information and gain access to opportunities that support advancement. Women in lower-status networks do not receive the same benefits.

While this is an incredibly simplified version of a very nuanced and complex problem, the key message is that the mechanisms that have created traditional organizational hierarchy, policy, and practice have also created echo chambers that disproportionately benefit men and hamper the advancement of women.8

What should women consider when building their network?

The research is great, but what does it mean, practically speaking, for women and how they build their network? For starters, it means understanding that networks – left to haphazardly build by chance – are likely to disproportionately negatively impact women. The good news is that women who use this information to intentionally build their network can increase their likelihood of advancement.

Research reveals there are four foundational principles (see Figure 1) women should keep in mind when building a professional network that can help them advance.9 These four foundational principles are critical for organizations to consider when designing initiatives to help women advance; we will discuss them in that context at further length later in the report. For more information on these four foundational principles, see the Appendix.

Figure 1: Four foundational principles women should follow when building their networks | Source: RedThread Research, 2019.

Are organizations considering networks today when trying to advance women?

Given the huge preponderance of research10 we’ve seen that points to the importance of networks in enabling women to rise, we began this research with high hopes of finding examples of organizations using network theory in their approach to advancing women. After all, there are decades of academic research11 on the topic of how networks differ among genders and how network status and power influence professional advancement. Further, most professionals are on various social networks that are technologically enabled, so our awareness of networks – and how they can be accelerated or changed by technology – is higher than ever. Therefore, it seemed logical that a number of organizations would be thinking about gender, networks, and how to use technology to help women rise.

We were wrong. After our 50 interviews with organizations of very different sizes, industries, and geographies, we found that relatively few organizations are thinking about how to help women design and build their networks intentionally. And even fewer are thinking about how to use technology to help. This was deflating.

However, all was not lost. Through our interviews, we gained significant insight into what organizations are doing today to advance women and found some examples of organizations tweaking common practices to account for network dynamics. We also uncovered a lot of existing technology that could help organizations evolve their existing practices to help with network dynamics. Further, we identified some novel practices that are showing early promise in advancing women.

In the pages that follow, we describe the common and novel practices for advancing women that we identified through our interviews. For all of these practices, we explain how network dynamics – in particular, the four foundational principles for women building their networks – play out. We further highlight the technology we think could help and give ideas for how new, yet-to-be-invented technology could assist in the future. We provide case examples wherever possible to bring the research to life.

Our hope is that this paper serves as a call to action for all leaders to re-think the practices and technology they use to advance women, and to much more substantially integrate an awareness of networks and how they play out differently for women into their efforts.

We know our connections matter. Both who we know and what those connections provide (information, resources, access, visibility) matters to career progression – so let’s make sure that women have the right connections that can help them advance. Our organizations’ future successes – and many women’s livelihood – depend on it.12

What are the Benefits and Risks of D&I Technology?

Posted on Tuesday, August 27th, 2019 at 9:42 AM

What are some of the obvious and less obvious risks of choosing and implementing D&I technology? In our recent study with Mercer, we examined the emerging market for D&I tech. As part of our exploration, we needed to take a step back to understand the potential gains or pitfalls that come when well-intentioned companies use technology and AI to solve endemic people challenges.

Here is an excerpt from that report which breaks down some of the risks and payoffs of implementing D&I tech:

What are the benefits and risks of D&I technology?

While there are many potential benefits of D&I technology, the most apparent one is the opportunity to create consistent, scalable practices that can identify or mitigate biases across organizations, often in real-time. Many people-related decisions leave a lot of room for bias, particularly when it comes to an assessment of a person’s skills, behaviors, or value (e.g., for hiring, performance evaluation, promotion, or compensation).

Much of the technology on the market today is designed to change the processes that enable bias or identify that bias exists. Another benefit customers see in D&I technology is the increased understanding of the current state of diversity and inclusion throughout the organization. With greater visibility, leaders can better measure and monitor the impact of D&I initiatives.

Benefits:

- Implementing more consistent, less-biased, and scalable people decision-making processes

Increasing the understanding of the current state of diversity and inclusion across the entire organization, using both traditional and new metrics - Measuring and monitoring the impact of efforts designed to improve D&I outcomes

- Raising awareness of bias occurring in real-time and at the individual level and enabling a range of people to act on it

- Enabling action at individual levels by making new, appropriate information available to employees at different levels within the organization

- Signaling broadly the importance of a diverse and inclusive culture to the organization

Risks:

- Implementing technology that itself may have bias due to the data sets on which the algorithms are trained or the lack of diversity of technologists creating it

- Creating legal risk if problems are identified and the organization fails to act

- Enabling the perception that the technology will solve bias problems, not that people are responsible for solving them

- Reducing people’s sense of empowerment to make critical people decisions

- Implementing technology or processes that are disconnected from other people processes or technologies

- Enabling employee perceptions of “big brother” monitoring, an over-focus on “political correctness,” or “reverse-discrimination”

Explore our interactive tool and infographic summary and download the rest of this report, including our detailed breakdowns of D&I tech categories and solutions, and some predictions for the future of this market. Also check out our most recent summer/fall 2019 update on the D&I tech market.