Articulating Invisible Information: Leveling the Playing Field

Posted on Monday, September 30th, 2019 at 5:43 AM

In the course of our research we identified two novel approaches to advance women. This article will focus on one of the two novel approaches; articulating invisible information.

Articulating invisible information

The second novel approach we identified in this research is the concept of articulating invisible information within the organization. One of the benefits of a high-status network is that unwritten knowledge is passed around. Therefore, a key way to advance individuals not in those high-status networks is to make that unwritten information visible. Put plainly, women need to have access to information about the opportunities within an organization, so they can effectively execute them. As one executive we spoke to put it,

“It’s about being intentional – as soon as you give women the information, they're perfectly capable of being aware and knowing what to do – versus the inequitable that took place in the past.”

However, relatively few organizations made note of this in our discussions, and fewer are taking action to bubble information to the surface and take it out of the informal hallway discussions among closed networks. Perhaps the greatest challenge with this practice is that organizations may not be aware of the information shared in closed, high-powered networks – and may not even have identified the high-powered network. Without this information, it can be hard to figure out what information should be made visible.

To that end, we suggest the following activities:

- Identify critical information in high-power networks

- Identify hidden information in low-power networks

- Document all the steps – both formal and informal – in promotion processes and share that information broadly

- Take steps to ensure everyone has access to critical information

1. Identify critical information in high-power networks

As we’ve noted below, there is a lot of critical information about how to be promoted and specific career opportunities to pursue available within high-power networks. To make this information more visible, organizations need to both identify high-power networks and to determine the critical information within them.

Organizations can use ONA, offered by companies such as Humanyze, Innovisor, Polinode, and TrustSphere, to uncover some of the hidden networks and the key influencers or connectors within those networks. For example, in Figure 1, we can see a network that has been colored by gender. This visual allows us to see the less connected networks (on the edges), who are the network brokers (the single nodes connecting networks) and the centrality of other networks (how central a node is within the map).

Figure 1: Example of a network map and different silos | Source: Polinode, 2019.

Once these networks are identified, traditional solutions (e.g., surveys, quick pulse polls, focus groups) can be deployed to understand what employees know about specific factors. For example, organizations may want to know what might influence career progression such as steps for being promoted, how to build support for promotion, and how to identify and access critical development opportunities. Organizations can identify this information and then take steps to make it visible and accessible to the appropriate levels and individuals across the organization through current technologies (e.g., SharePoint sites). Another approach is to leverage some of the social networking sites (e.g., Guild, Fairygodboss, or Fishbowl, mentioned earlier) to share some of this promotion information more broadly. Finally, interventions that purposely connect people within one network to another (action learning projects, cross-functional projects, internal gig-work, matched mentorship or sponsorship) could help with the sharing of critical information.

There are plenty of other opportunities for technology to be used to make information in high-power networks visible in the future. For example, we have seen prototypes of technology that will automatically flag relevant job posts to employees, highlighting job opportunities that women may not know about from their network or based on their own research. In addition, there are some technologies (e.g., from Visier, Fuel50, and PageUp People) that highlight, given a specific position, career paths people have taken within the organization. We could foresee that technology being focused specifically for women, helping them see the paths of other women in the organization and illustrating how some of the most senior women in the organization rose. We could also see organizations opening internal blogs or videos to leaders to talk more transparently about how they were promoted and the keys to their rise (highlighting broadly previously hidden information).

2. Identify hidden information in low-power networks

Interestingly, another type of “hidden” information in organizational networks is who should be promoted or identified as a HIPO but are not because they are not members of a high-status network. There is relatively new technology available to help organizational leaders uncover this information. For example, SAP SuccessFactors’ has a feature that enables HR and leaders, during the calibration process, to identify if someone has been a high performer for a certain period of time, but not been promoted (see Figure 2). This is especially a challenge for women, because research shows they are more likely to be rated as high performers than men, but less likely to be promoted.

Figure 2: SAP SuccessFactors’ calibration flags for performance and promotion | Source: SAP SuccessFactors, 2019.

Other technologies can help identify if women are underrepresented within the HIPO pool. As shown in Figure 3, SAP SuccessFactors provides leaders with a way to compare the total representation with the representation levels in the HIPO pools. In this example of photo-less calibration, you can see the overall population is roughly 38% women, but that no women are identified as high-potential. While this may be known (and potentially appropriate) within a certain group, these technologies can make visible this type of trend across broader swaths of the enterprise. It can also provide an opportunity to re-examine the women who are deemed high-performing and understand what is preventing them from also being labeled high-potential.

Figure 3: SAP SuccessFactors’ analysis of HIPOs by gender | Source: SAP SuccessFactors, 2019.

3. Document all the steps – both formal and informal – in promotion processes and share that information broadly

Once the critical information regarding promotion processes is documented, it is important to share that information broadly so that individuals in lower-power networks can access it. Almost every organization we spoke to highlighted their use of basic technologies (e.g., Skype, SharePoint) to share at least some information about promotion or succession processes. However, the challenge is that sometimes the information is too generic or focuses too much on the formal processes instead of the information activities and behaviors necessary for promotion.

4. Take steps to ensure everyone is receiving information regularly

While this suggestion seems terribly simple, it can still make a big difference. At its essence, this suggestion is to make sure that all the appropriate individuals are being looped into emails, chats, and meetings. It is easier for someone to “forget” someone who needs a communication if they are not perceived as being in the high-power network.

In the course of our interviews, one simple hack to address this problem was shared: to make email lists (e.g., “Senior Leadership Team”) that include everyone, so that women aren’t left off the list when emails are being sent. As one woman stated,

“When the Senior Leadership Team (SLT) email list was used, I would get all the communications. If people added people by name, inevitably at least one of us women would get left off the communication.”

There are technological solutions that can help with this issue of communication equality. For example, one technology, offered by Humanyze, can show who is receiving emails or meeting notifications versus who would be expected to receive those notifications, given the group’s gender representation. For example, in Figure 4, we can see the amount of communications via email by gender. The black line indicates the representation level within the group (e.g., for Finance, approximately 50% of the team is women). However, within that Finance group, 70% of the email communications is between men. This could show that women are not being included in important email communications. This same sort of analysis can be done for meeting invitations or chat interactions.

Figure 4: Humanyze’s analysis of communication frequency by gender | Source: Humanyze, 2019.

Another technology, Worklytics, tries to address this challenge by offering email-based nudges for other people to include in a specific email or work event invitation. This technology works by generating a list of the most important work events1 in an organization (e.g., key meetings, shared documents, projects, and email threads) and then scoring each work event for diversity by looking at the relative number of differing demographic groups involved in the event. By tracking the average diversity of the organizations most important work events, Worklytics can provide a sense of the level of access to key opportunities for growth within an organization or sub-group. (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Worklytics analysis of meeting attendance, by gender | Source: Worklytics, 2019.

We’ve mentioned a lot of vendors in this section. Figure 6 summarizes those we included. Please note, a list of all vendors included in this report is in the Appendix.

Figure 6: Vendors included in articulating the invisible section | Source: RedThread Research, 2019.

Gig-work Marketplaces: A Novel Way to Advance Women

Posted on Wednesday, September 25th, 2019 at 4:44 PM

Gig-work marketplaces

During our conversations, it was often suggested that the way to advance women was to help them gain access to meaningful work in which they can collaborate with new peers and connect with diverse groups and leaders to showcase their abilities. As it turns out, there can be significant challenges to doing this both for employees within organizations and for people who are trying to rejoin the workforce. To that end, we suggest organizations consider

- Implementing internal gig-work marketplaces

- Leveraging external gig-work marketplaces

1. Implementing internal gig-work marketplaces

While some organizations have rotational programs or stretch assignments, those interventions do not tend to be broadly available or clearly communicated. Thus, many women are stuck within their existing roles without a way to meaningfully broaden their network and skill set.

To address this situation, we’d like to suggest organizations consider using internal gig-work1 marketplaces as an alternative option for women to diversify their network and to show themselves as energizers within their networks. Typically, these marketplaces are seen as part of organizations’ learning and development efforts. However, we think they could play an important role in helping to advance women as they could provide a way for women to broaden their network outside of their current team, showcase their openness to new ideas and concepts, and gain new skills through meaningful new opportunities.

What is an internal gig-work marketplace?

Gig-work marketplaces provide a place within the organization where individuals with small projects can find other employees interested in working on those projects. Therefore, anyone else in the organization who may have some extra time can potentially contribute to this work, while the person doing the work can engage with new people in a meaningful way and learn new skills. The projects are typically shorter in length and represent work that can easily be partitioned into discrete sections. The project owner interviews individuals interested in doing the work and makes the decision of who works on the project. The person wishing to do the project typically needs to get their manager’s approval to take on the additional work. The project posting process is typically enabled by technology and made centrally available.

Of course, there are potential pitfalls. For example, if organizations, leaders and individual women do not carefully consider the type of gig-work they provide and accept, it can result in a lack of substantive advantage in terms of new skills or career development and progression. Further, without planning, there is no guarantee that these projects will connect individuals to the right networks or create visibility into a woman’s capabilities. Simply having a platform or process that connects people to work doesn’t cultivate relationships and grow networks. Organizations need to create some structure to help leverage these opportunities into visibility, connection, and relationships.

Internal gig-work marketplaces tend to be enabled through technology that is available across the organization. Some of the organizations we interviewed have leveraged Sharepoint or built in-house platforms to provide a more systematic, standardized approach.

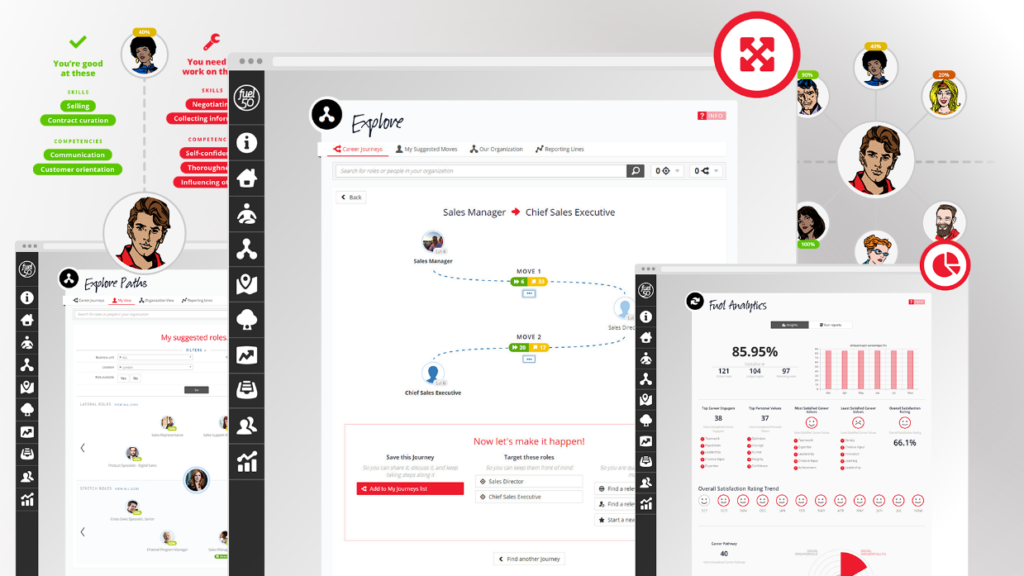

While some organizations2 create their own in-house solutions, vendors are providing solutions that help organizations build an internal gig-work platform as well. For example, Fuel50 (see Figure 1) recognizes the importance of creating a career-agile workforce. Their solution helps individuals not only identify current skill levels but also articulate what is important to them and their career. This information helps individuals and leaders identify opportunities that align with career interests, experiences, and the things that drive and energize them in their careers.

The platform suggests roles (new positions or gig opportunities), but more importantly it gives individuals visibility to all the developmental gig assignments across the organization. It also gives leaders data-based insights on their talent across the organization on real, meaningful assignments.

Figure 1: Determining career energizers and tapping into gig-work with Fuel50 | Source: Fuel50, 2019.

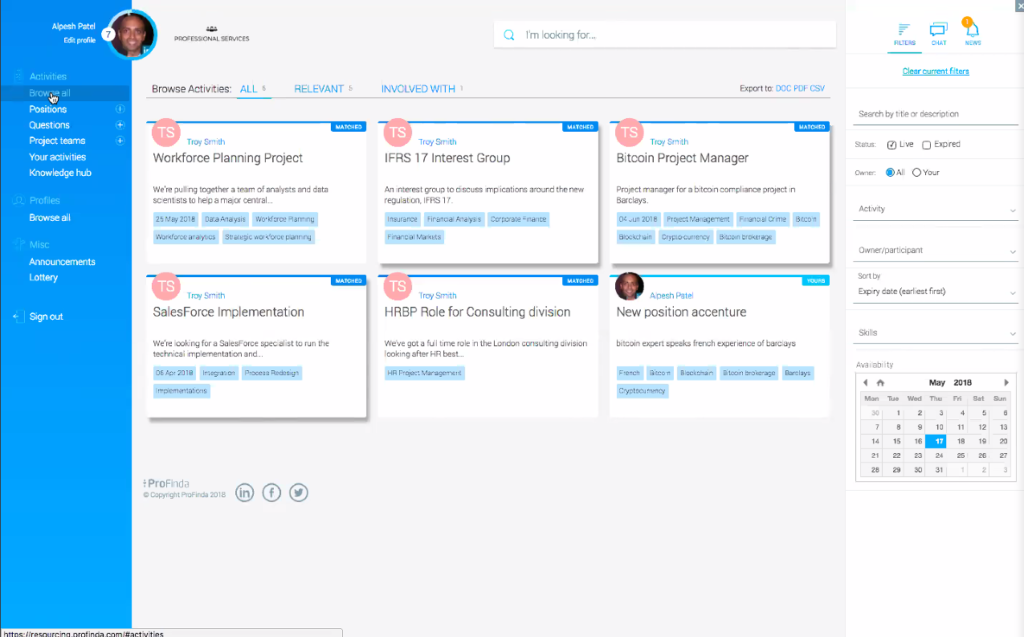

Another vendor, Profinda, takes a network-based approach in their offering and matches people to potential projects based on skills. The vendor offers an internal talent marketplace that allows people to see projects coming available and to apply for them. In addition, the solution also helps organizations identify when an individual will be available for a new assignment (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Profinda’s skill-based matching | Source: ProFinda, 2019.

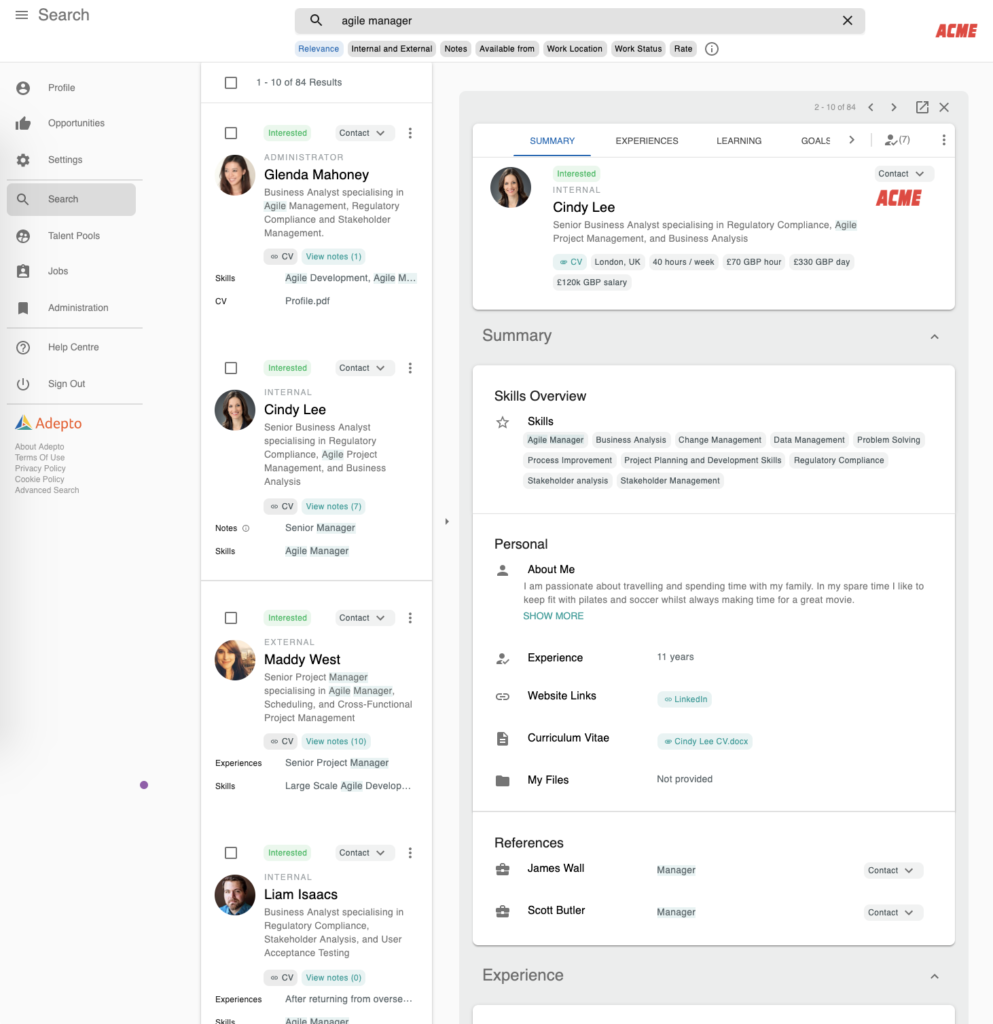

Still yet another vendor, Adepto, offers what they call a “skills based total talent platform” for a single enterprise, providing insight into “all the talent available… internal and external; past, present and future.” Users can search for individuals by skills, experiences, or qualifications, while workers build their profiles within the system, highlighting that same information and their career/skill aspirations. This type of visibility could make it easier for women to find new opportunities, and critically, make it easier for leaders to access a broader pool of talent for both full-time and project-based work (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Adepto’s search and profile interface | Source: Adepto, 2019.

This type of technology is not exclusive to new(er) players in the technology landscape. Workday has created a talent marketplace that aims to help organizations identify and develop non-traditional talent and SAP SuccessFactors has features that can be used for a similar purpose.3

In the future, organizations could look at how many women are asking for additional assignments in their development process but are not being given these or are given stretch assignments that are less meaningful than their male colleagues.

2. Leveraging external gig-work marketplaces

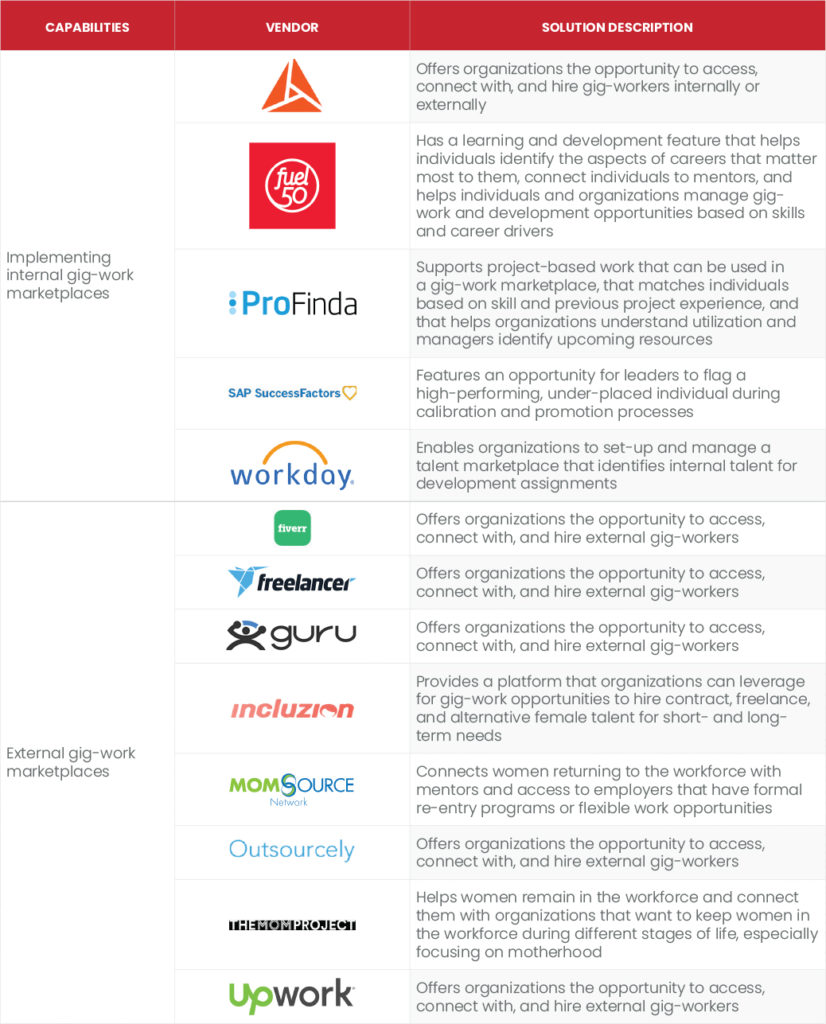

External gig-work marketplaces are much more well-known than internal gig-work marketplaces. With these, organizations can either post projects or search for workers who have the required skills, experiences, or qualifications. Some of the more well-known gig-work platforms include Upwork, Fiverr, Guru, Freelancer.com, and Outsourcely.com.4

There is increasingly a niche for diversity-related gig-work platforms. With these platforms, women (or other diverse individuals) can identify organizations that are prioritizing diversity, find projects that are of interest, meet individuals who could be interested in helping them move into the organization, and show their skills and capabilities. In particular, this type of technology could be leveraged for women who are returning to the workforce after an extended break or who have challenges with finding the right organization or network to get started again. This technology can also connect organizations to a diverse talent pool that they would not have been able to purposefully access in the past.

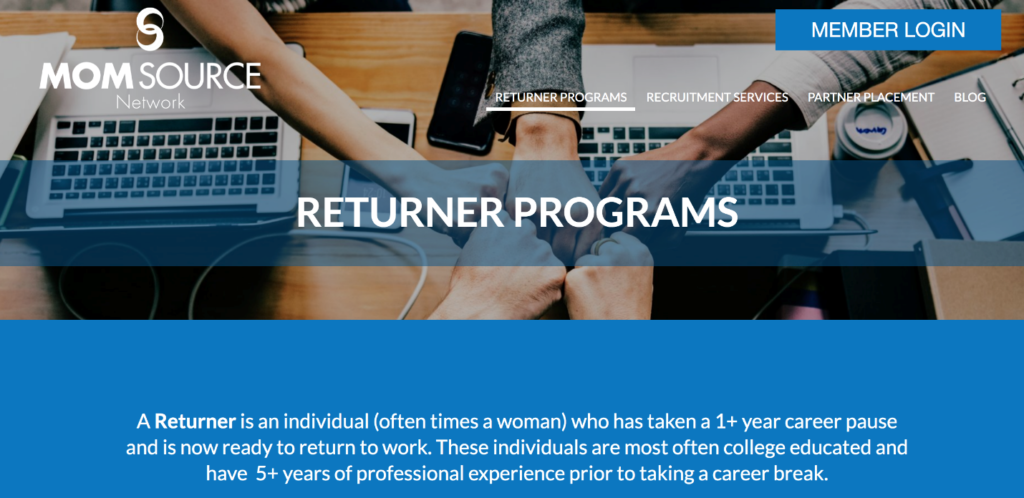

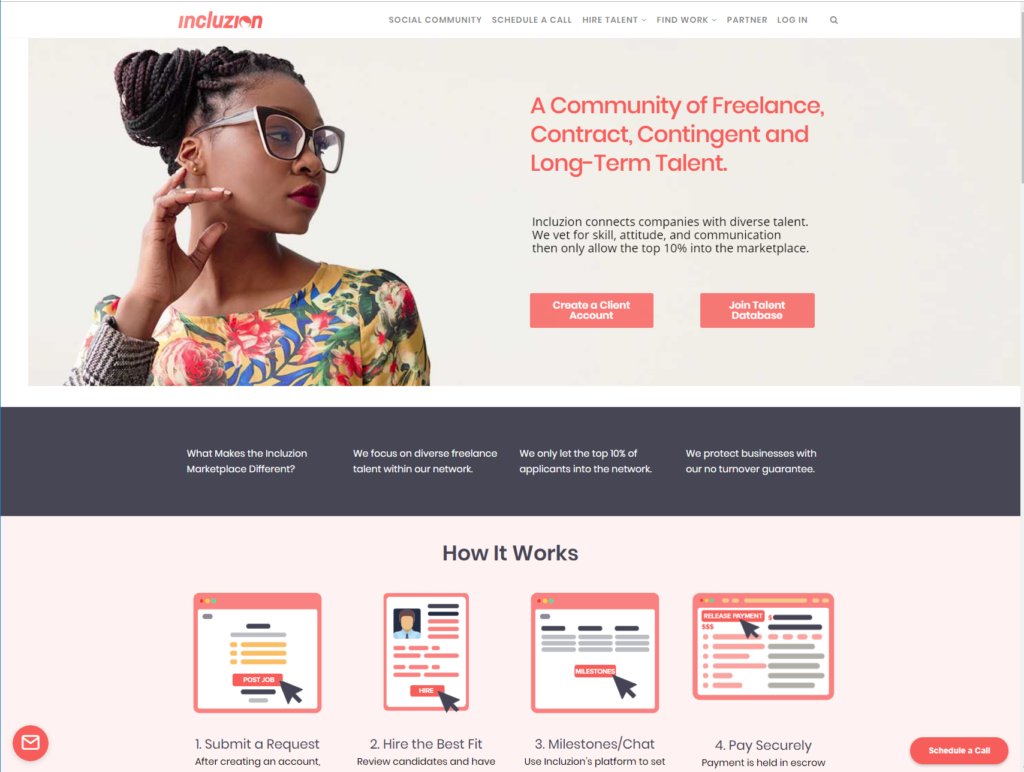

There are a range of tools available on the market. For example, Mom Source Network and The Mom Project are both working to develop deep talent pools that organizations can tap into. Mom Source Network specifically offers resources as well as access to job postings to people who are returning to work from an extended break (see Figure 4). The Mom Project creates Maternityships®5 which are time-bound opportunities for new talent (likely another woman who is trying to connect with the organization and gain meaningful skills) to fill a role in the organization while another woman is out on maternity leave. Incluzion.co is another gig-work marketplace, but they focus across all diversity characteristics (see Figure 5). All these solutions are designed to help diverse talent gain new skills and experiences while expanding their network and showcasing their abilities.

Figure 4: Screenshot from Mom Source Network | Source: Mom Source Network, 2019.

Figure 5: Incluzion.co’s gig-work marketplace | Source: Incluzion.co website, 2019.

We’ve mentioned a lot of vendors in this section. Figure 6 summarizes those we included.

Figure 6: Vendors included in the gig-work marketplace section | Source: RedThread Research, 2019.

Networks and Gender: Why Do We Care?

Posted on Thursday, August 29th, 2019 at 4:20 PM

Efforts to improve women’s representation in leadership are decades old, yet the numbers remain stubbornly low:

- For every 100 men promoted, only 79 women are promoted1.

- Approximately 40% of women in senior roles/technical positions report being one of the only women in the room2.

- The World Economic Forum3 estimates it will take 168 years for North America to close the global gender gap.

So, why don’t we see more women in leadership?

There are many potential answers to the question of why women do not rise at equal rates as men. However, of all the potential solutions, our research identified one we think deserves more attention than it has received to date: women are not gaining access to the information and opportunities they need from their professional networks in order to advance.

Our network connects us to the right groups, people, and information and inclusion at work – through our networks – can be a critical factor that influences promotion and advancement opportunities. Unfortunately, research indicates 81% of women report some form of exclusion at work, yet 92% of men don’t believe that they are excluding women at all4. This difference highlights the critical, yet less obvious influence of our professional networks.

Based on our interviews, women tend to advance when three conditions are present:

- People work with them and experience them as equally competent professionals.

- They are given access to opportunities and experience.

- They are included in conversations and have access to information at the right level.

Focusing on networks can help with all these things. More specifically, networks – and the information they carry – are one of the primary ways people learn about career advancement and development opportunities. By being in the right networks, women have an opportunity to work alongside and for others who would support them in their advancement. They also have access to high-quality opportunities and can have the conversations that help them advance.

However, research suggests that women and men's networks – and the information within them – are different. Understanding these connections between people – who knows whom and why – could help organizations understand why some employees rise and why others do not.

How are men and women’s networks different and why does it matter?

Traditional social dynamics – along with promotion rates, power, and rank – influence the creation and composition of professional networks.5,6 In general, as men move up the ranks in organizations, they join higher-status networks with more information and power. They also are more likely to be surrounded by men, because men, statistically speaking, are more likely to be promoted. Women – who tend to be promoted at lower rates – more often find themselves in lower-status networks (which can be women-dominated).

Network status influences the extent to which someone has access to key conversations, information, and projects that would help them advance in an organization.7 Since men tend to be in those high-status networks, they tend to have access to higher-quality information and gain access to opportunities that support advancement. Women in lower-status networks do not receive the same benefits.

While this is an incredibly simplified version of a very nuanced and complex problem, the key message is that the mechanisms that have created traditional organizational hierarchy, policy, and practice have also created echo chambers that disproportionately benefit men and hamper the advancement of women.8

What should women consider when building their network?

The research is great, but what does it mean, practically speaking, for women and how they build their network? For starters, it means understanding that networks – left to haphazardly build by chance – are likely to disproportionately negatively impact women. The good news is that women who use this information to intentionally build their network can increase their likelihood of advancement.

Research reveals there are four foundational principles (see Figure 1) women should keep in mind when building a professional network that can help them advance.9 These four foundational principles are critical for organizations to consider when designing initiatives to help women advance; we will discuss them in that context at further length later in the report. For more information on these four foundational principles, see the Appendix.

Figure 1: Four foundational principles women should follow when building their networks | Source: RedThread Research, 2019.

Are organizations considering networks today when trying to advance women?

Given the huge preponderance of research10 we’ve seen that points to the importance of networks in enabling women to rise, we began this research with high hopes of finding examples of organizations using network theory in their approach to advancing women. After all, there are decades of academic research11 on the topic of how networks differ among genders and how network status and power influence professional advancement. Further, most professionals are on various social networks that are technologically enabled, so our awareness of networks – and how they can be accelerated or changed by technology – is higher than ever. Therefore, it seemed logical that a number of organizations would be thinking about gender, networks, and how to use technology to help women rise.

We were wrong. After our 50 interviews with organizations of very different sizes, industries, and geographies, we found that relatively few organizations are thinking about how to help women design and build their networks intentionally. And even fewer are thinking about how to use technology to help. This was deflating.

However, all was not lost. Through our interviews, we gained significant insight into what organizations are doing today to advance women and found some examples of organizations tweaking common practices to account for network dynamics. We also uncovered a lot of existing technology that could help organizations evolve their existing practices to help with network dynamics. Further, we identified some novel practices that are showing early promise in advancing women.

In the pages that follow, we describe the common and novel practices for advancing women that we identified through our interviews. For all of these practices, we explain how network dynamics – in particular, the four foundational principles for women building their networks – play out. We further highlight the technology we think could help and give ideas for how new, yet-to-be-invented technology could assist in the future. We provide case examples wherever possible to bring the research to life.

Our hope is that this paper serves as a call to action for all leaders to re-think the practices and technology they use to advance women, and to much more substantially integrate an awareness of networks and how they play out differently for women into their efforts.

We know our connections matter. Both who we know and what those connections provide (information, resources, access, visibility) matters to career progression – so let’s make sure that women have the right connections that can help them advance. Our organizations’ future successes – and many women’s livelihood – depend on it.12